Artist Frances Gynn and musicians Lona Kozik and Sam Richards comprise Hallsands Arts (https://www.hallsandsarts.co.uk/). Their responses to Hallsands in South Devon, its history and present landscape, both in individual works and collaborations, are the basis of Hallsands Revisited.

Conversation between Frances Gynn (FR), Lona Kozik (LK) and Sam Richards (SR).

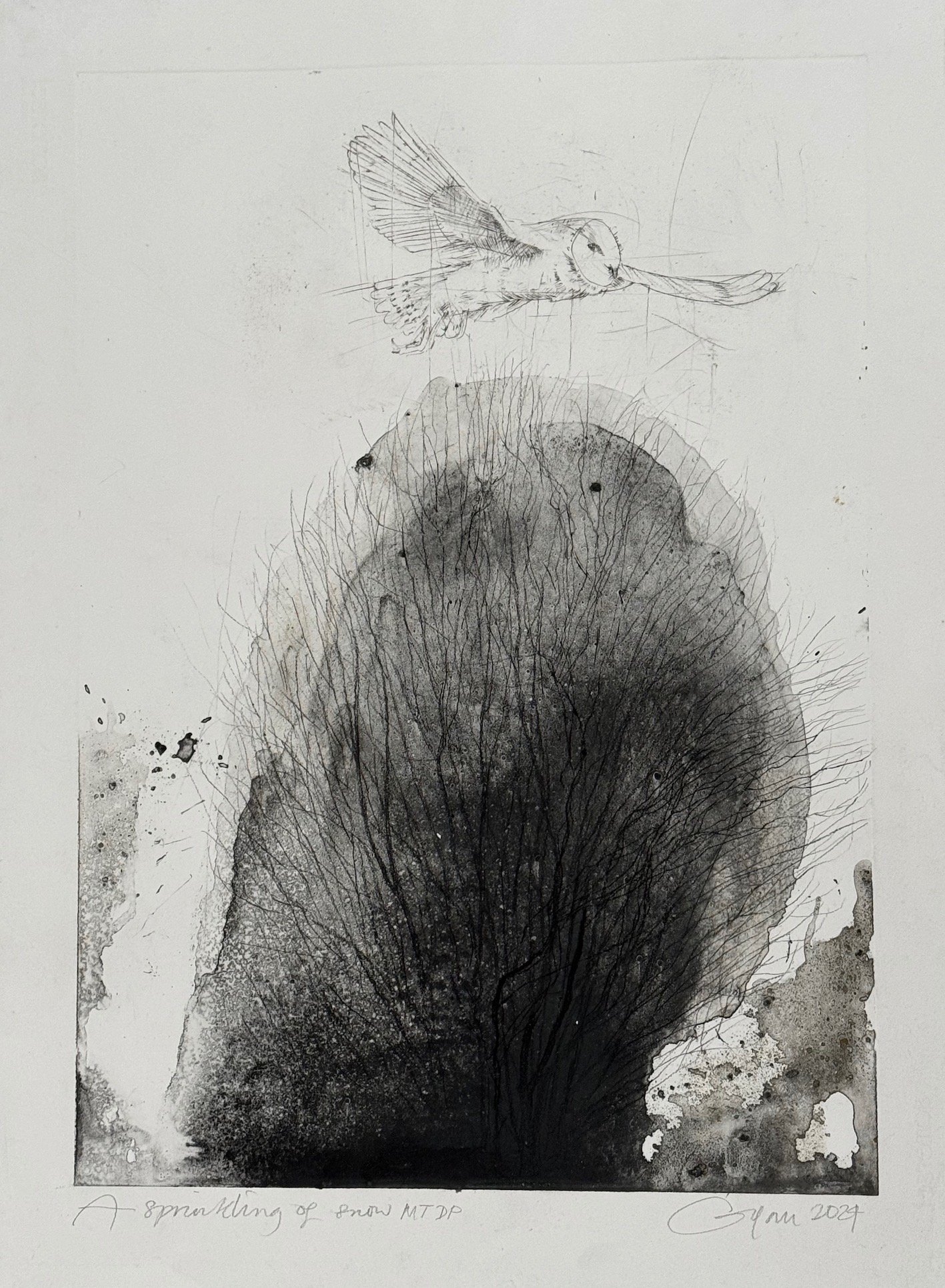

I once made an album called “Love Among the Ruins”, stealing the title (but not the content) from the 1894 Burne-Jones painting. I was fascinated by the way ruins have a beauty of their own derived in large part from what is no longer there. From absence. Hallsands is very much a living ruin in that it changes frequently and visibly as more and more of it gets washed away into the sea. Despite the tragedy of its demise – or maybe because of it – I find it quite beautiful. (SR)

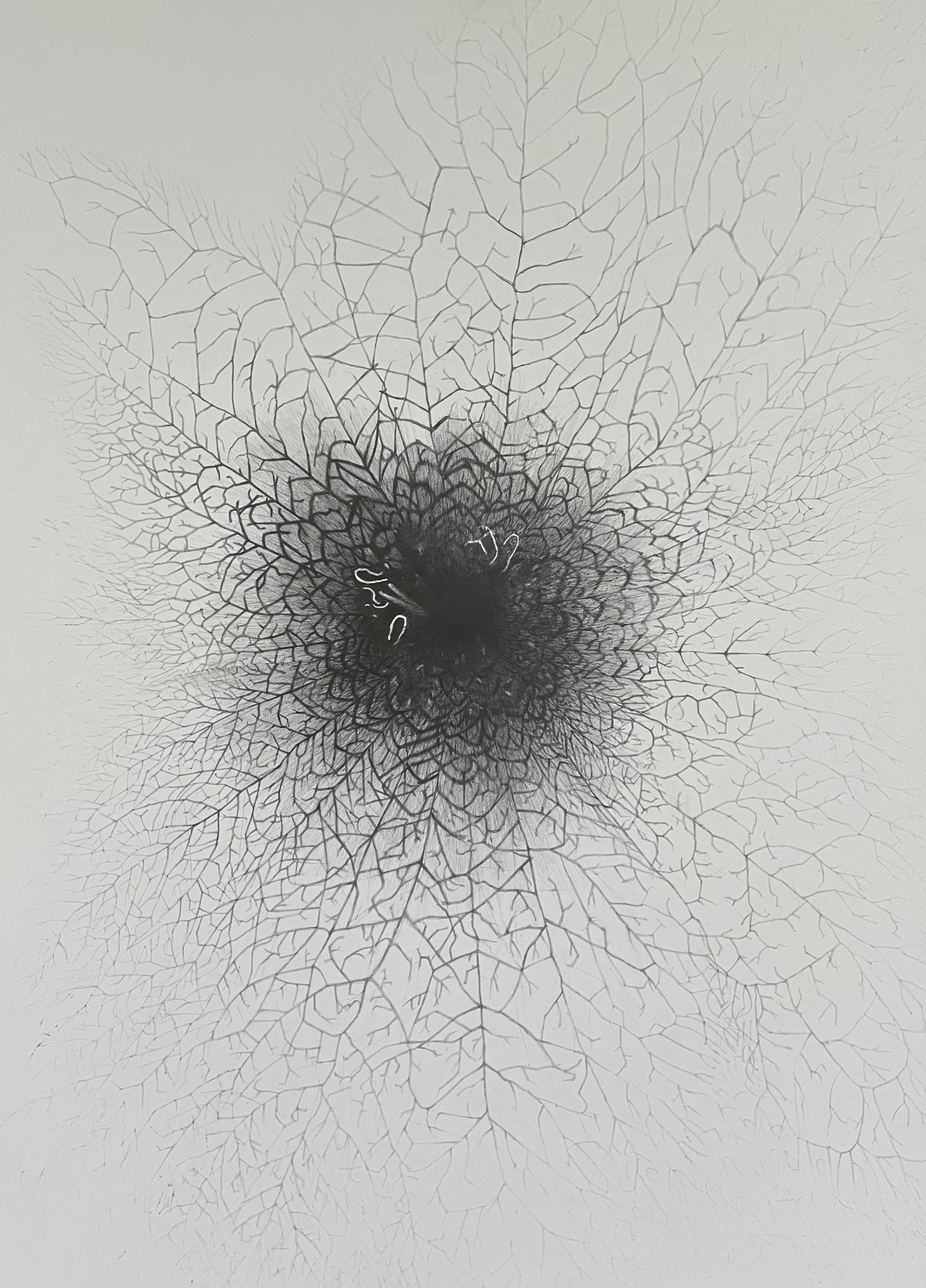

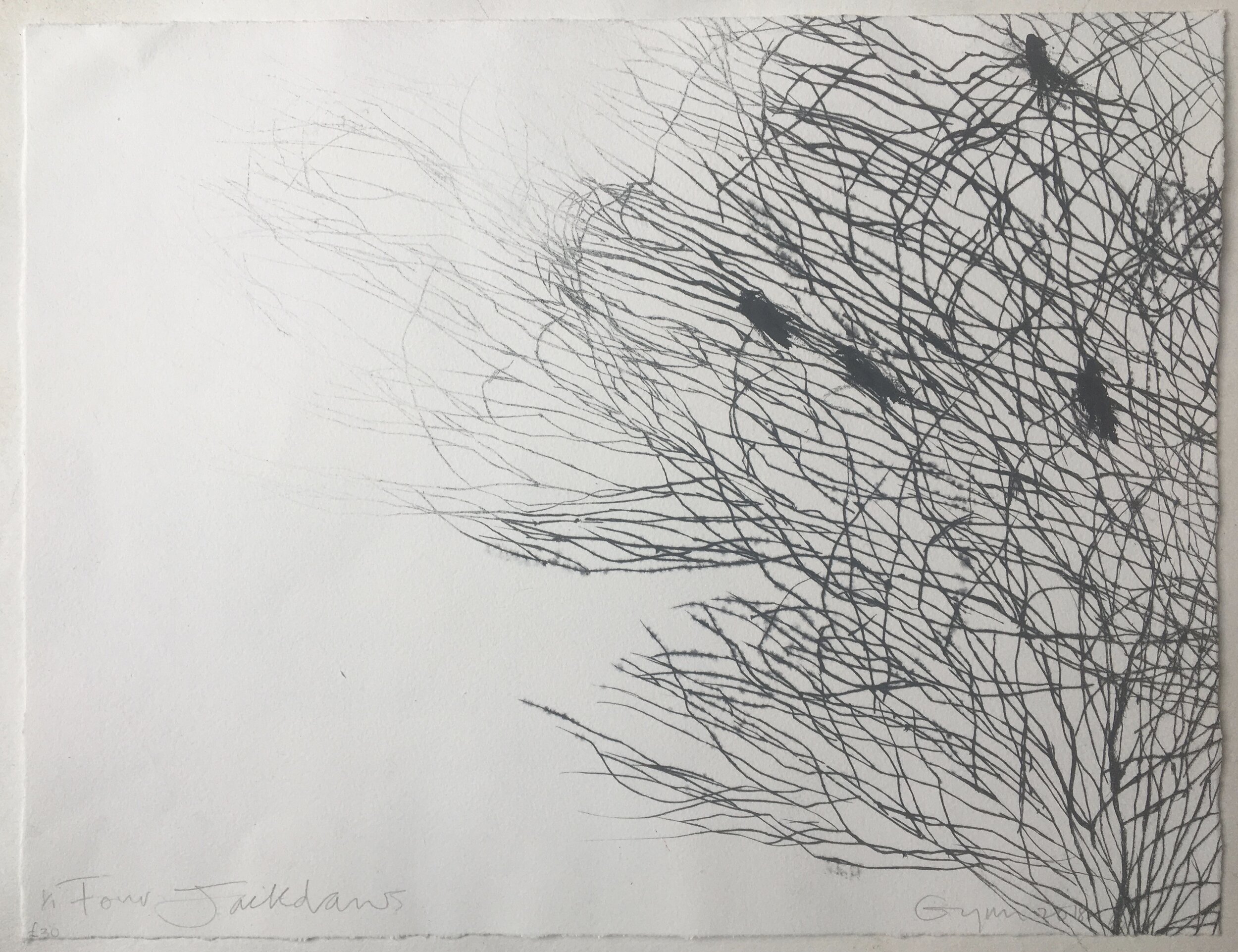

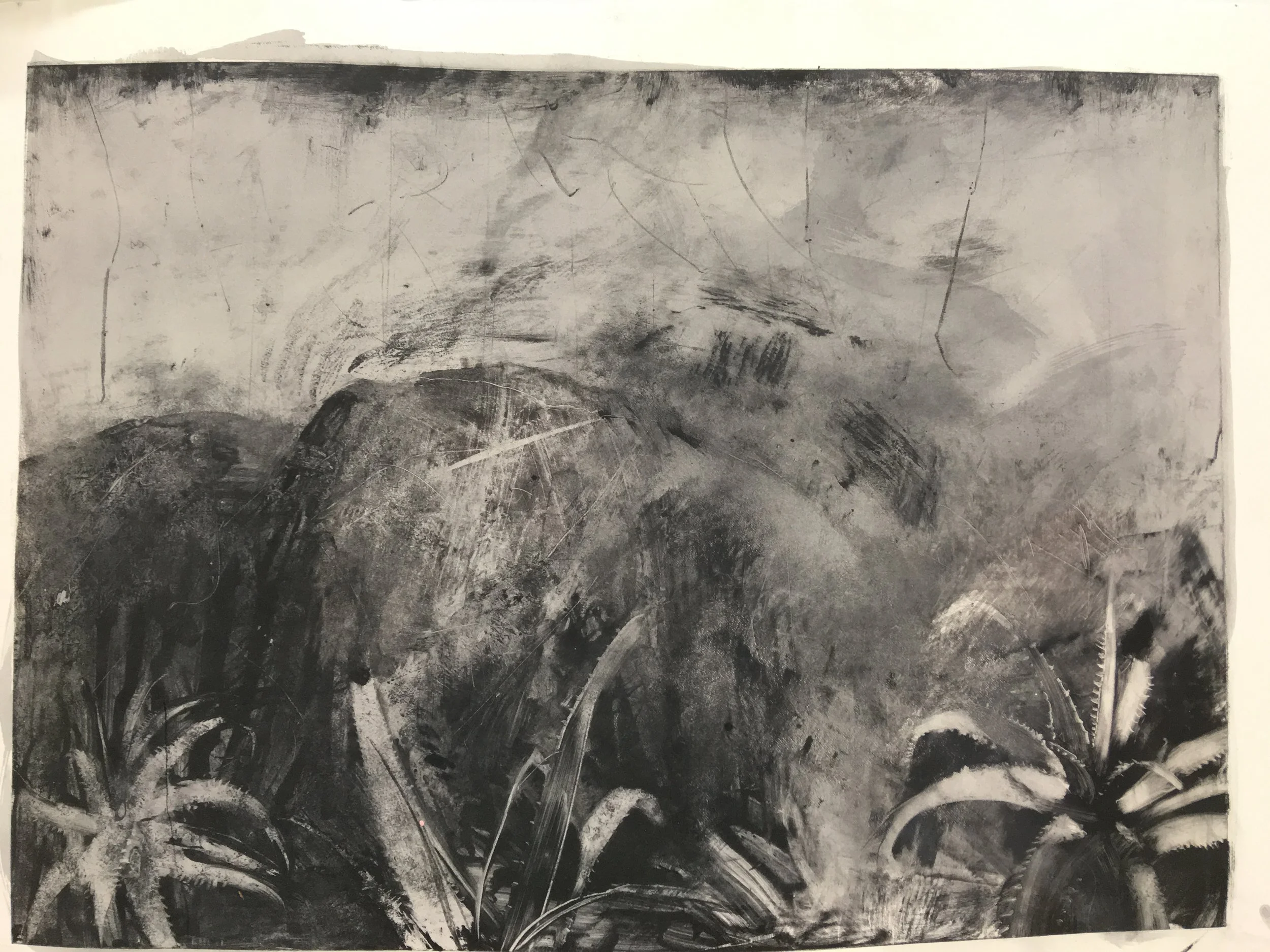

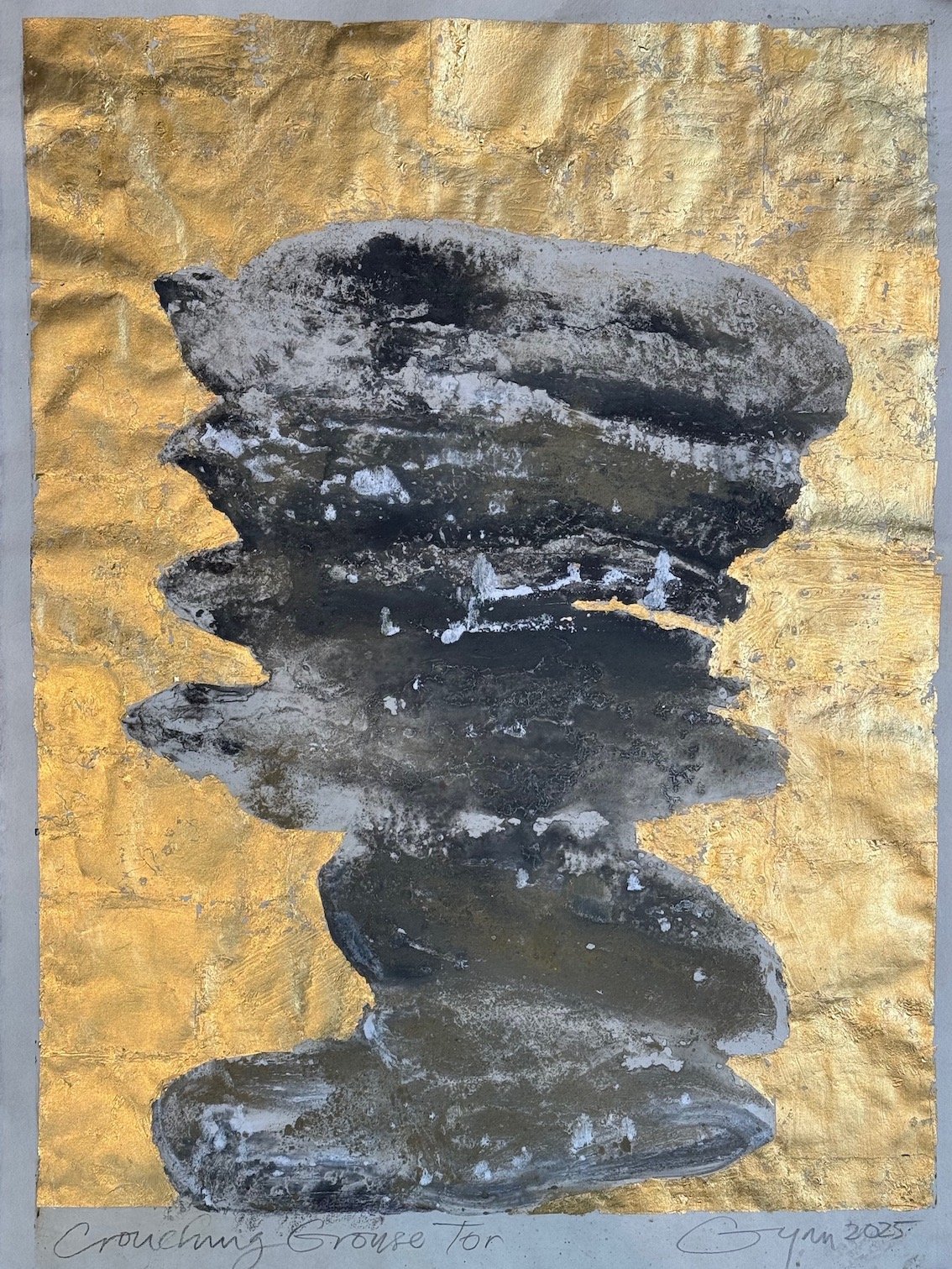

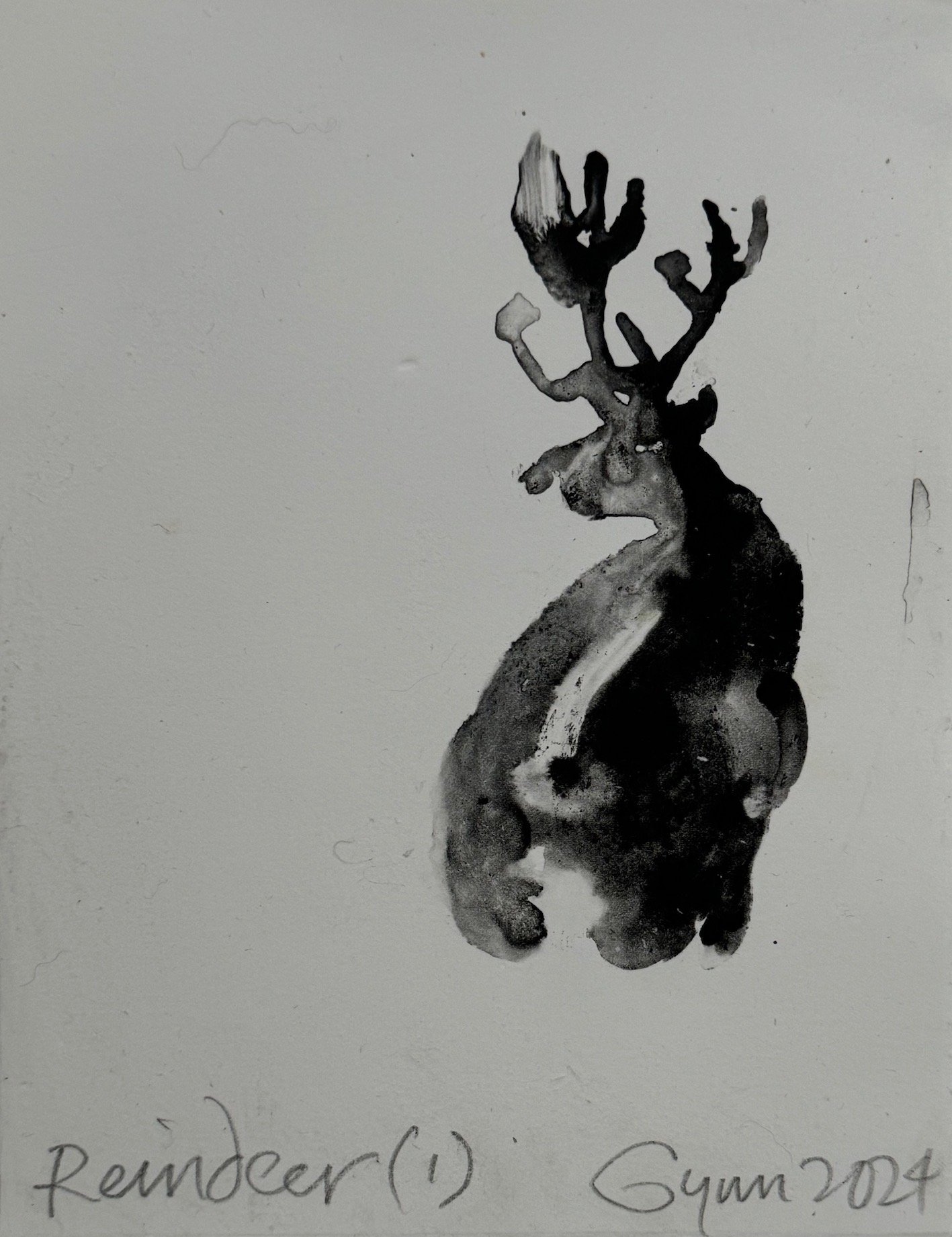

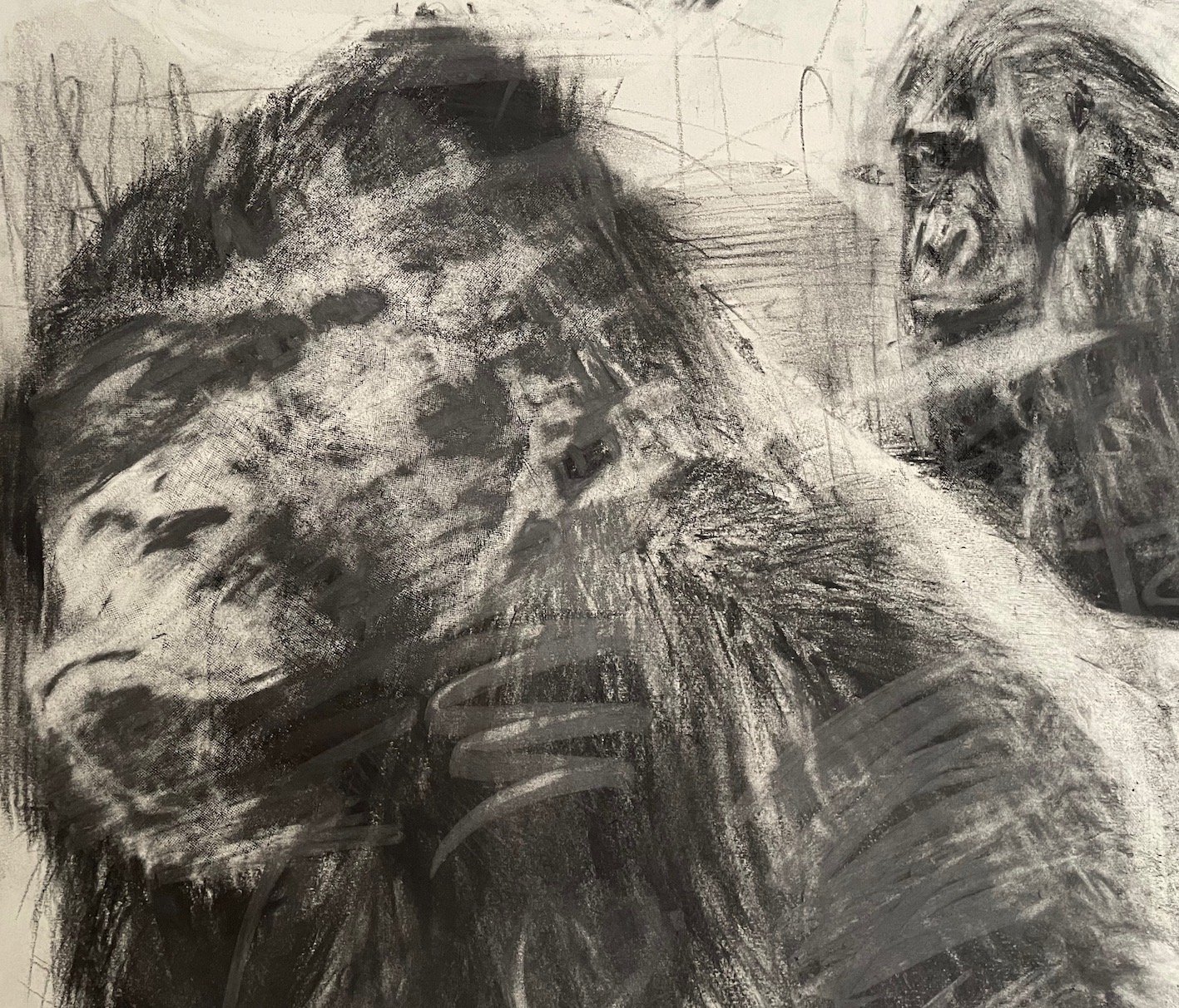

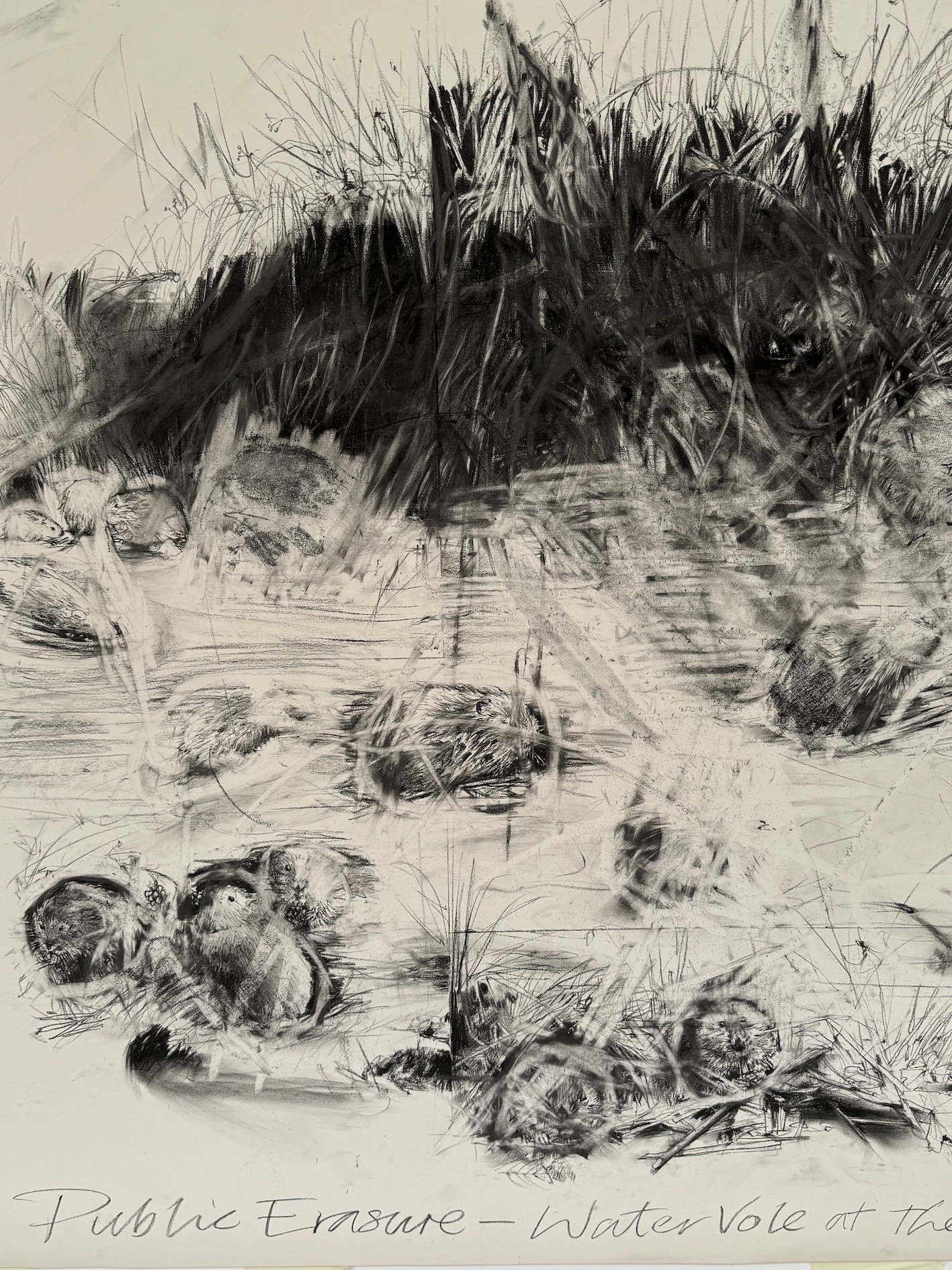

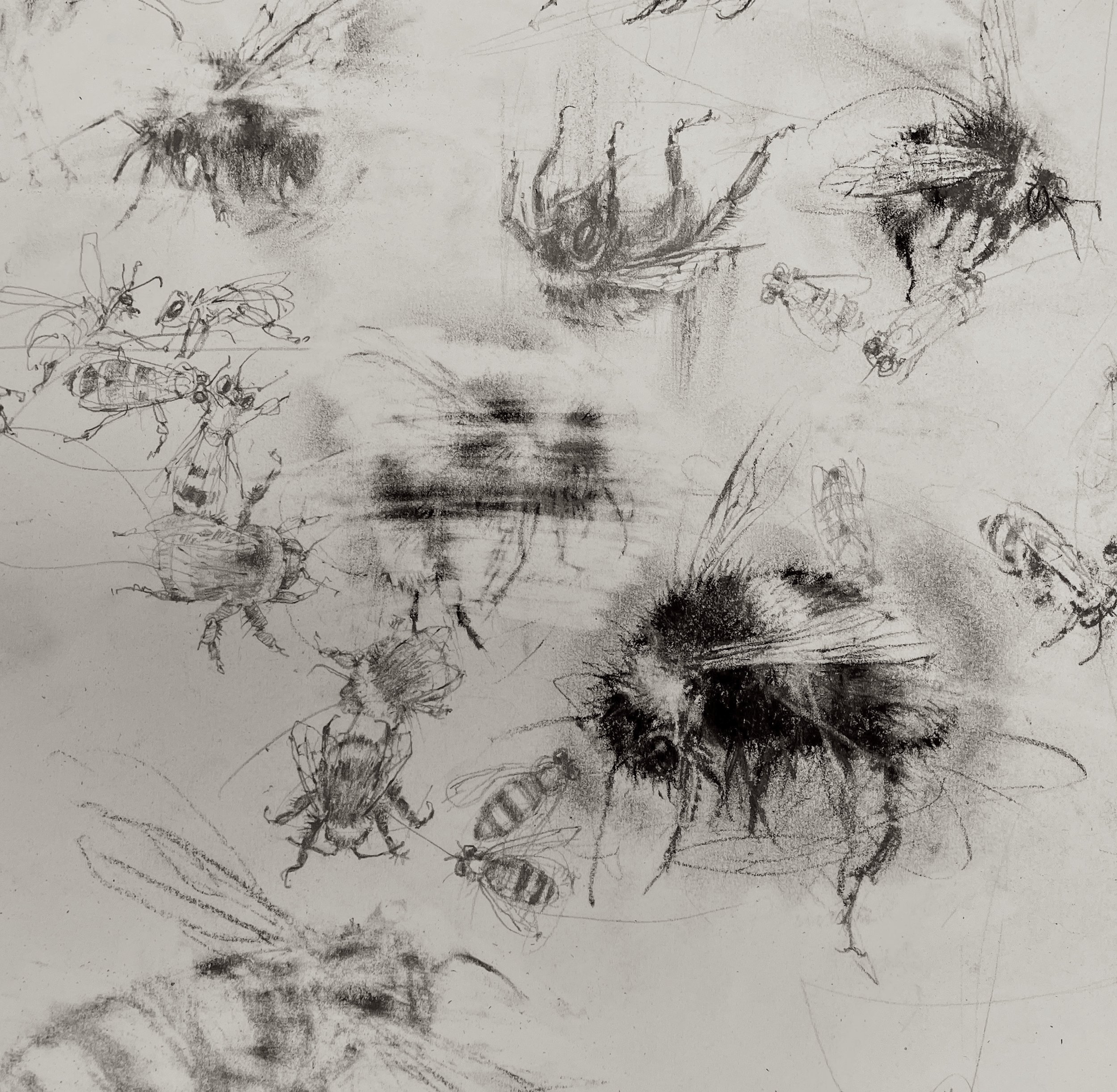

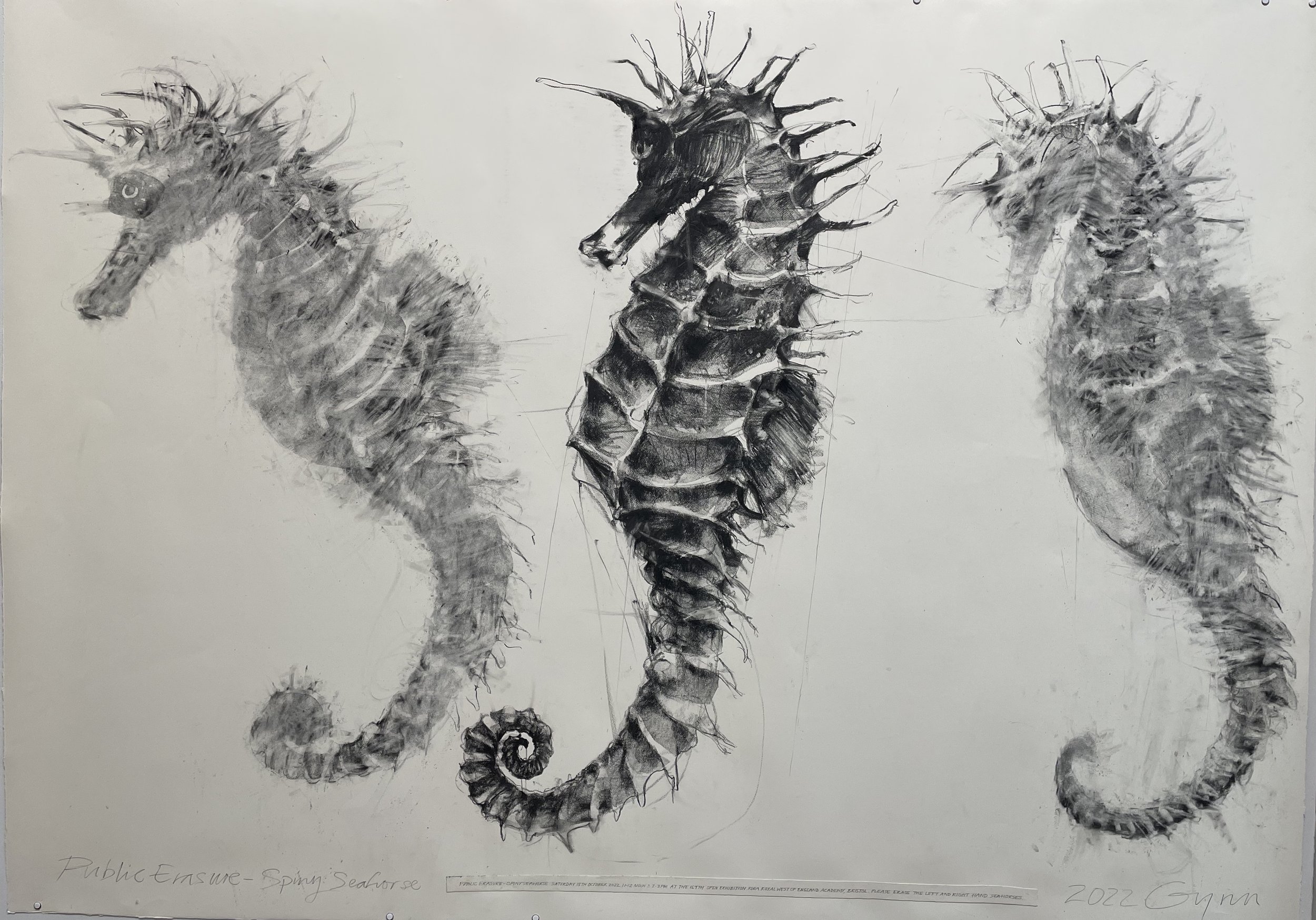

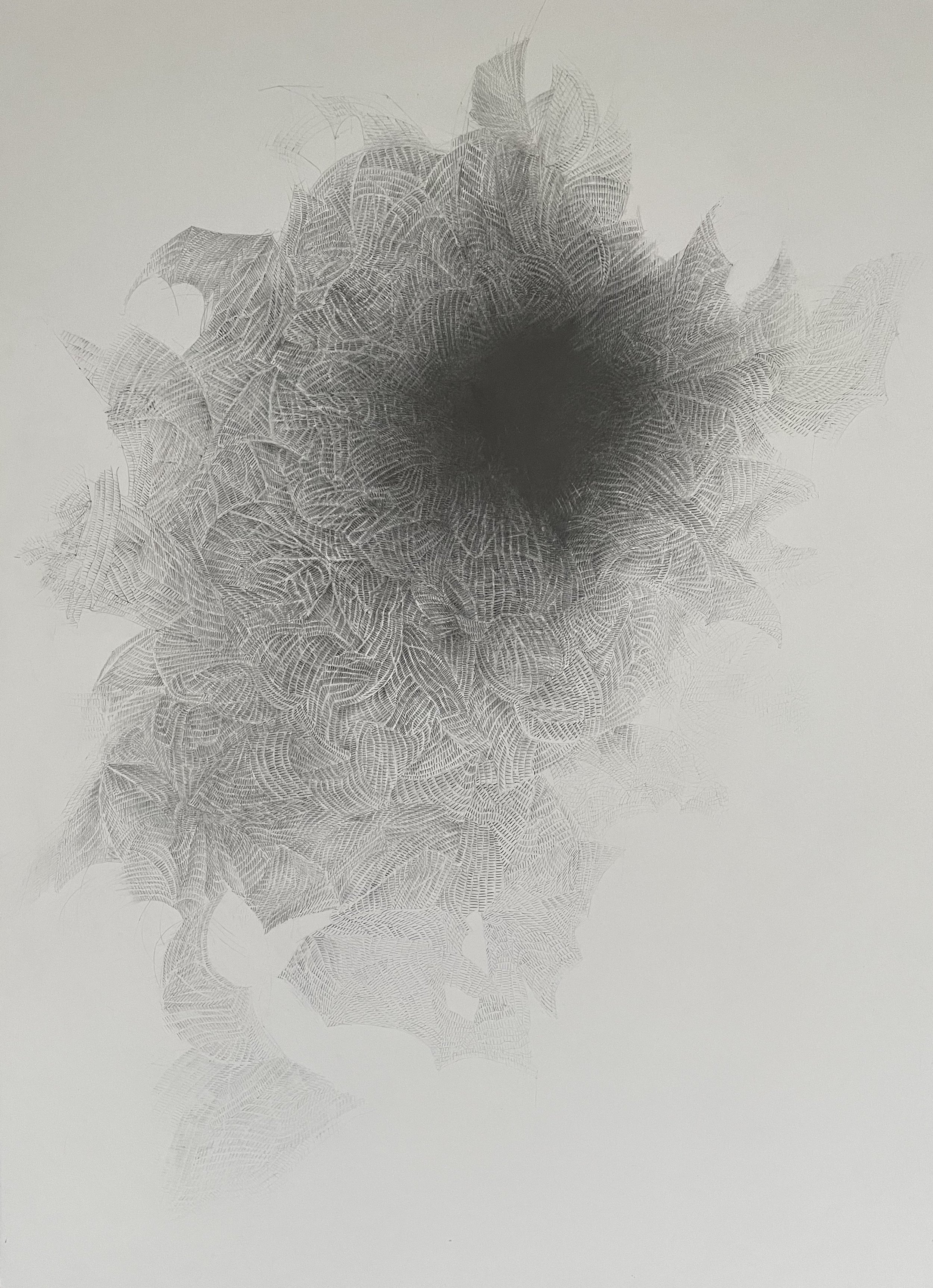

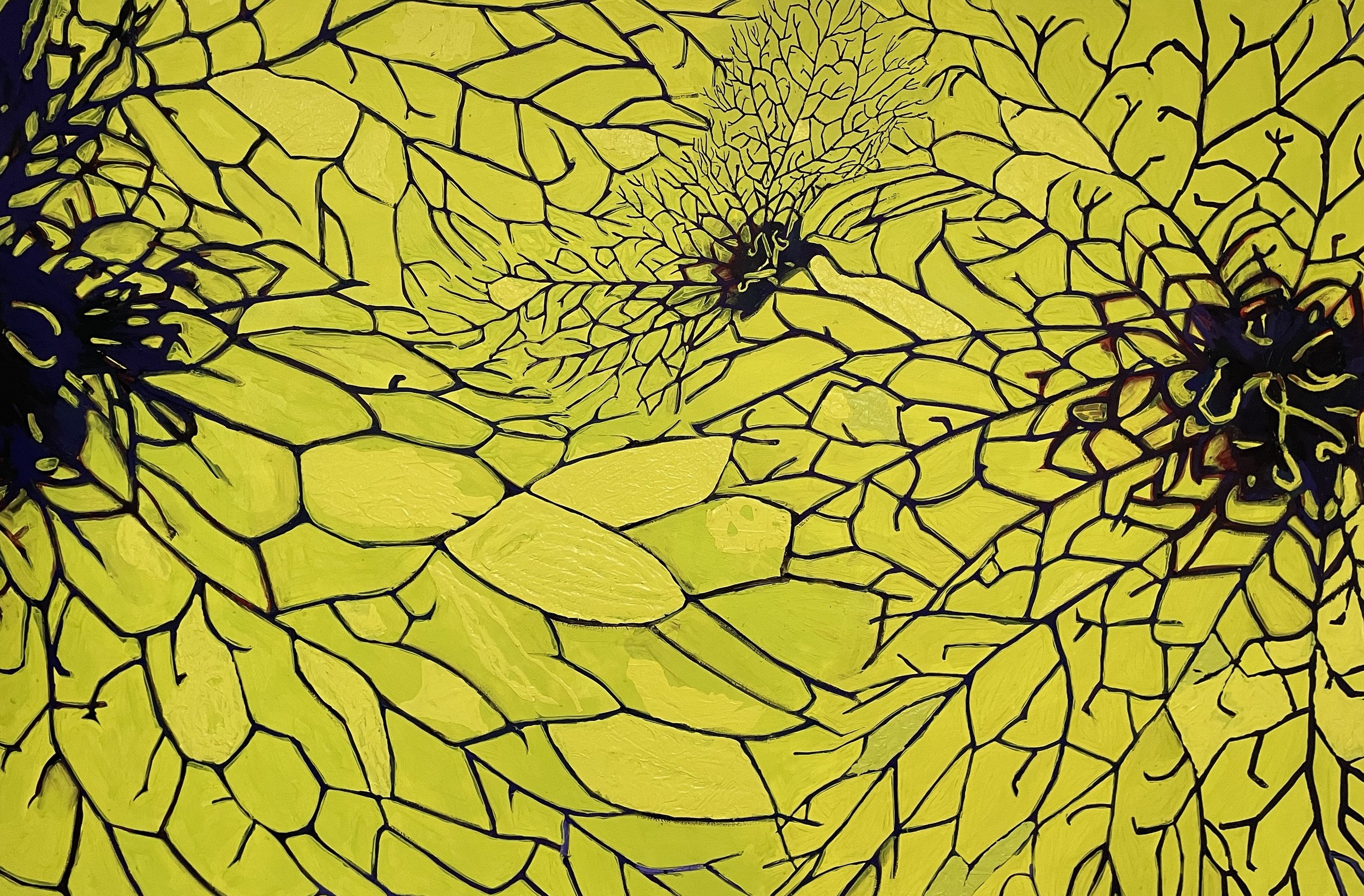

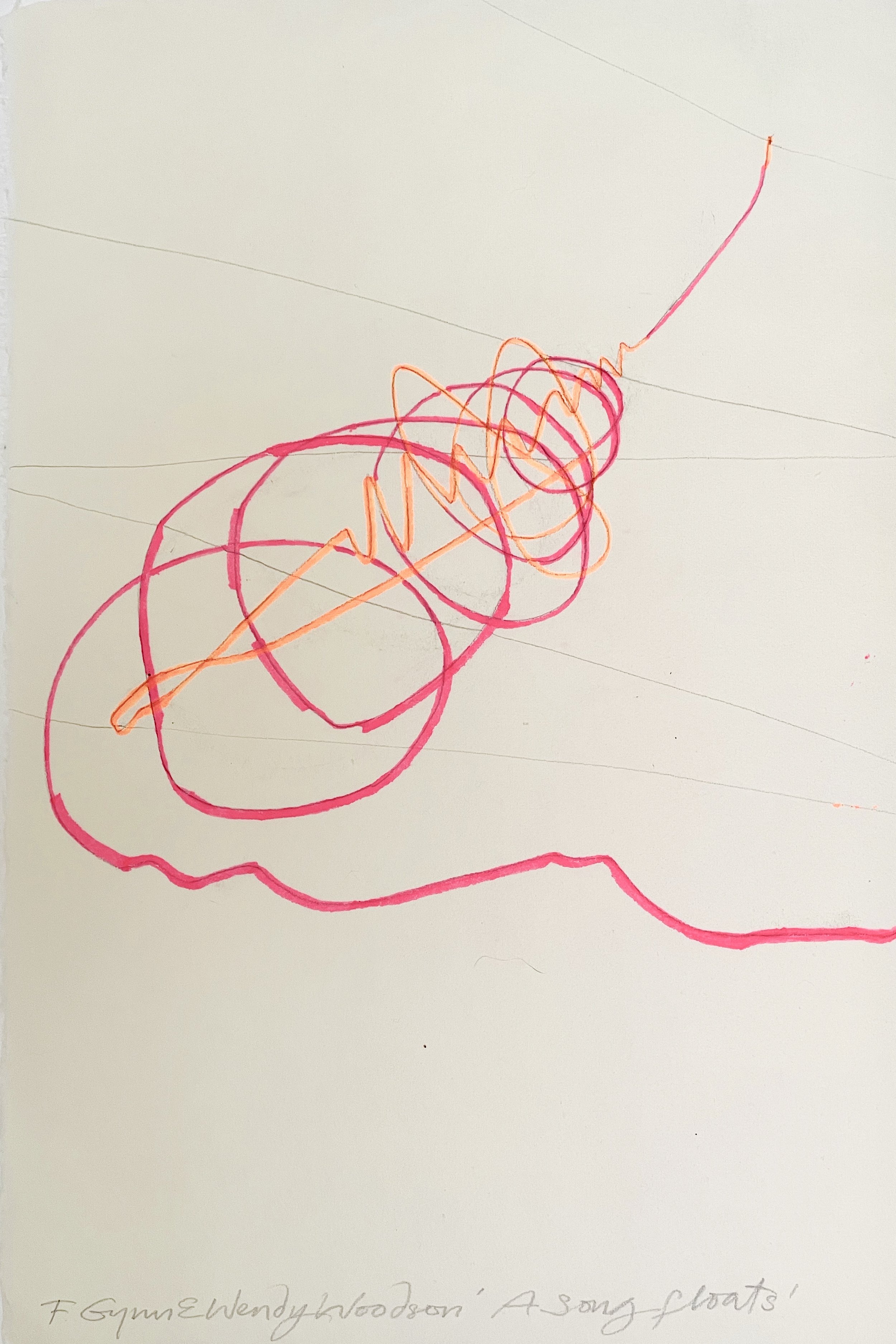

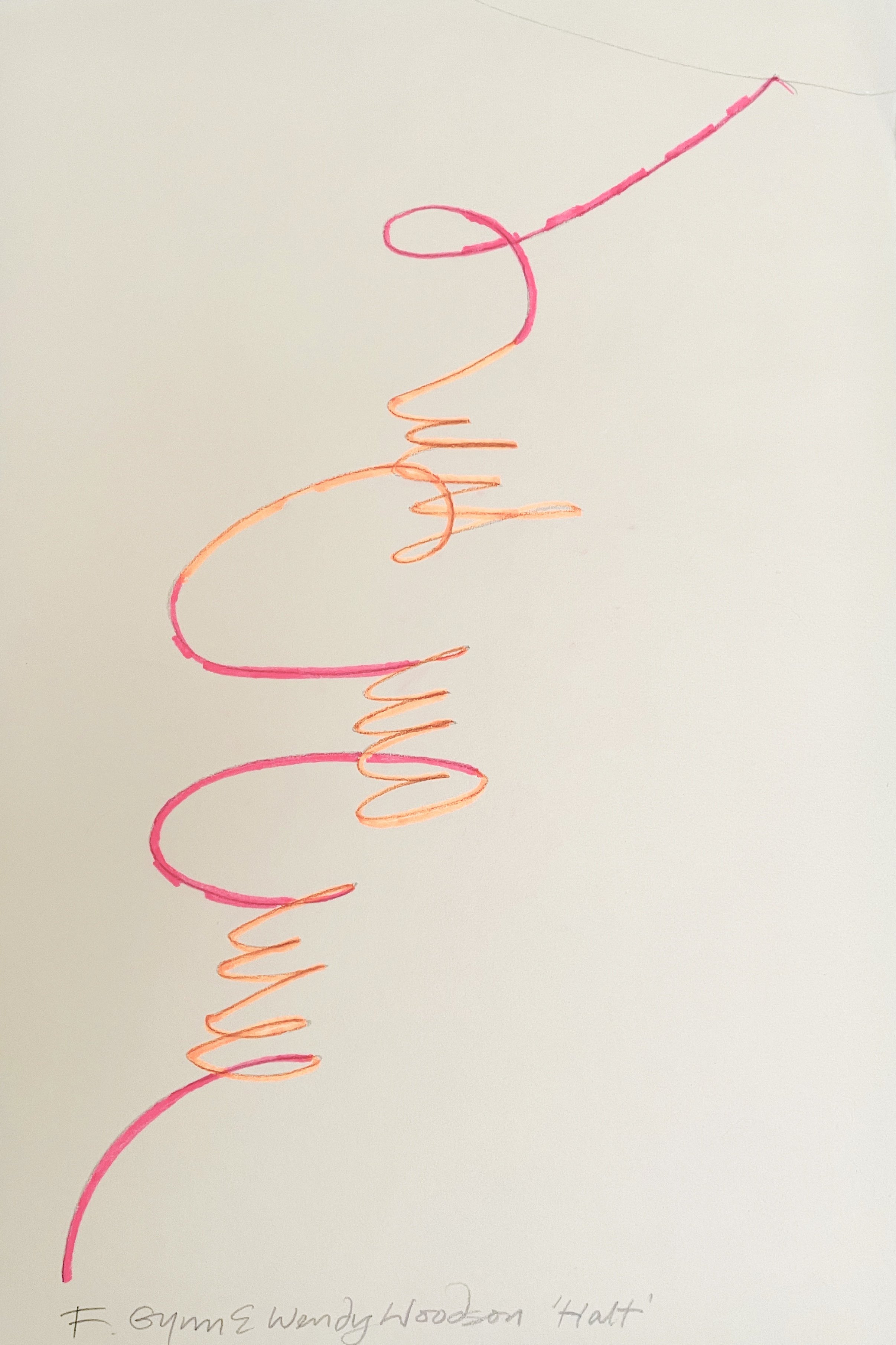

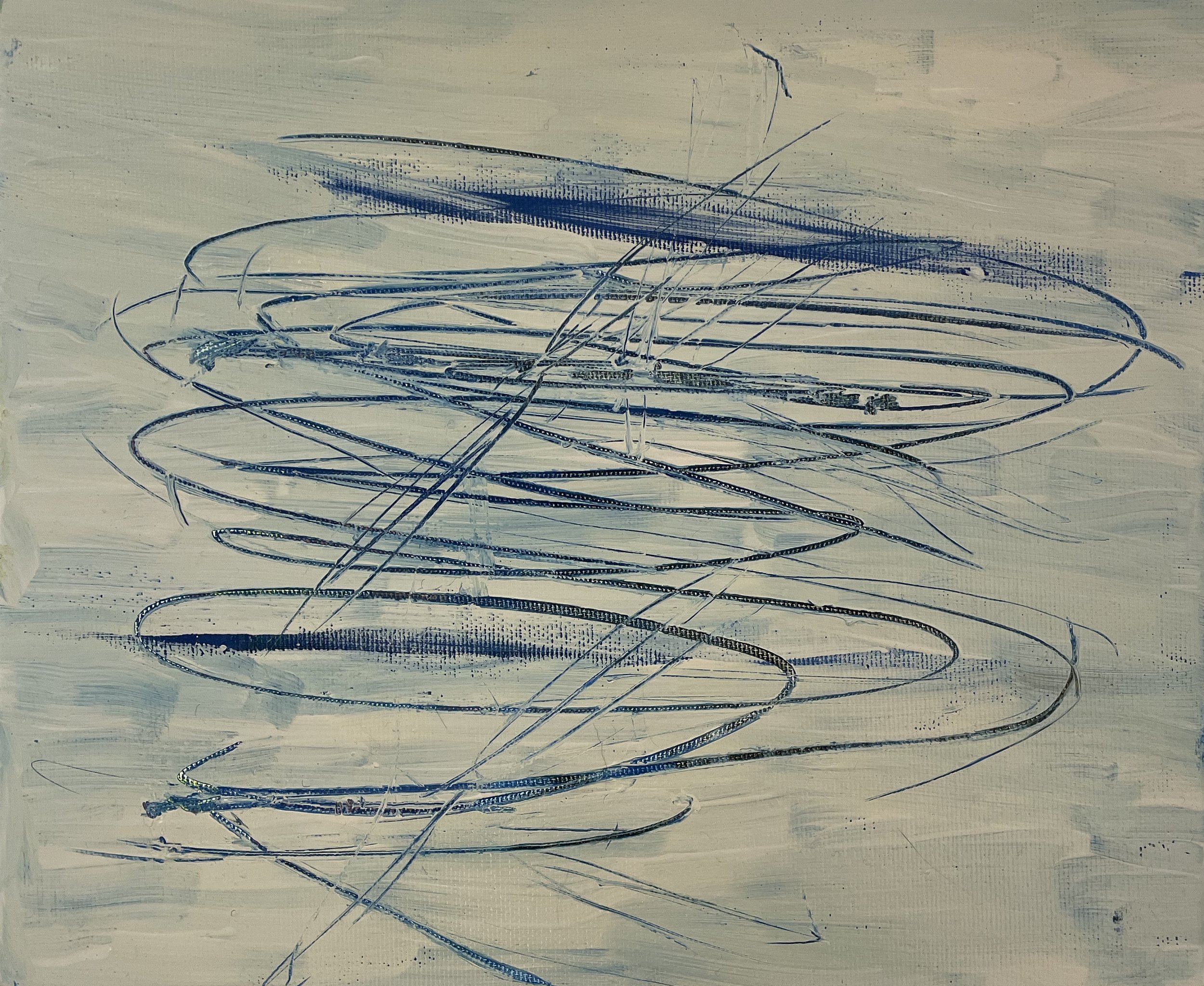

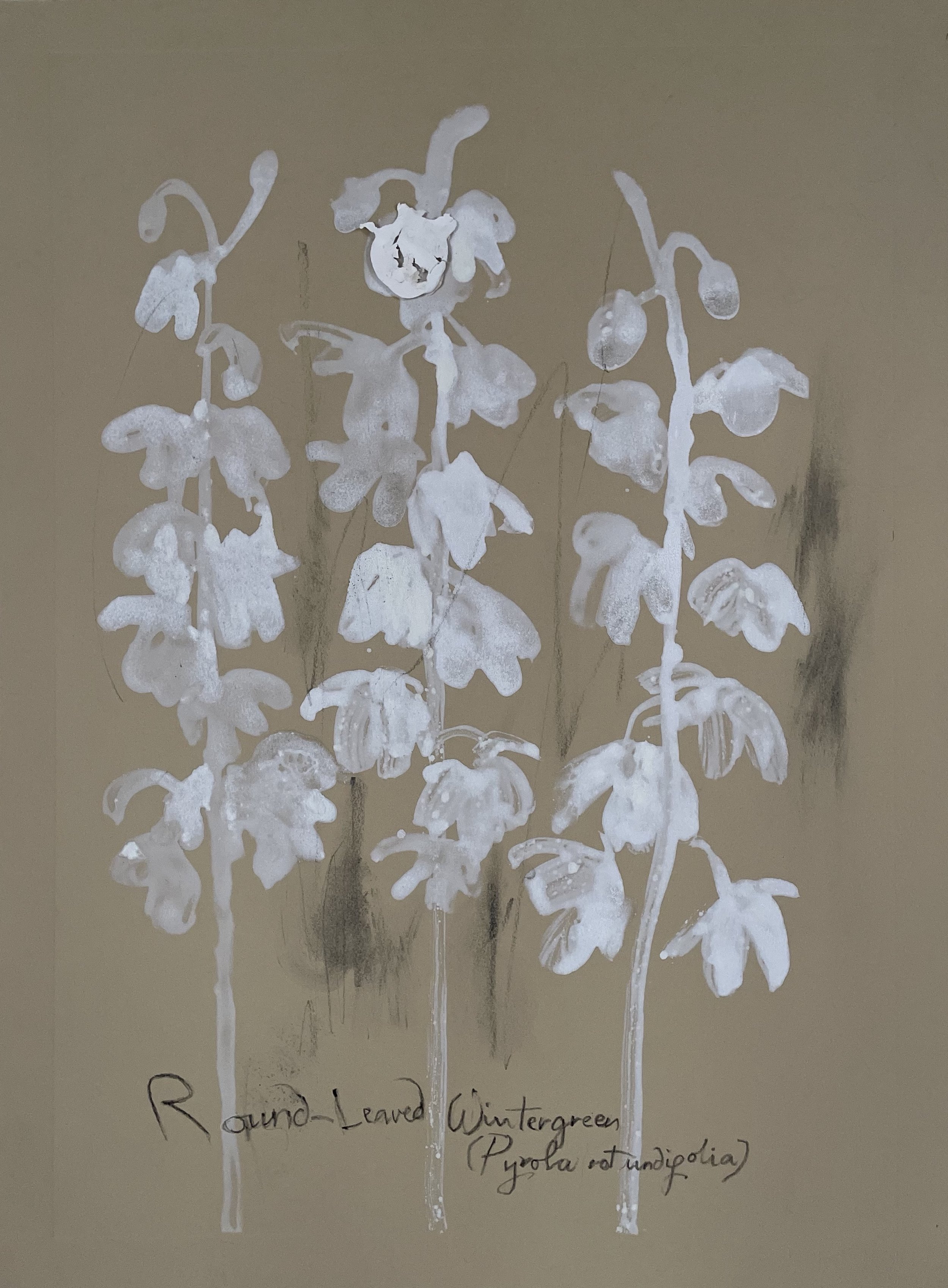

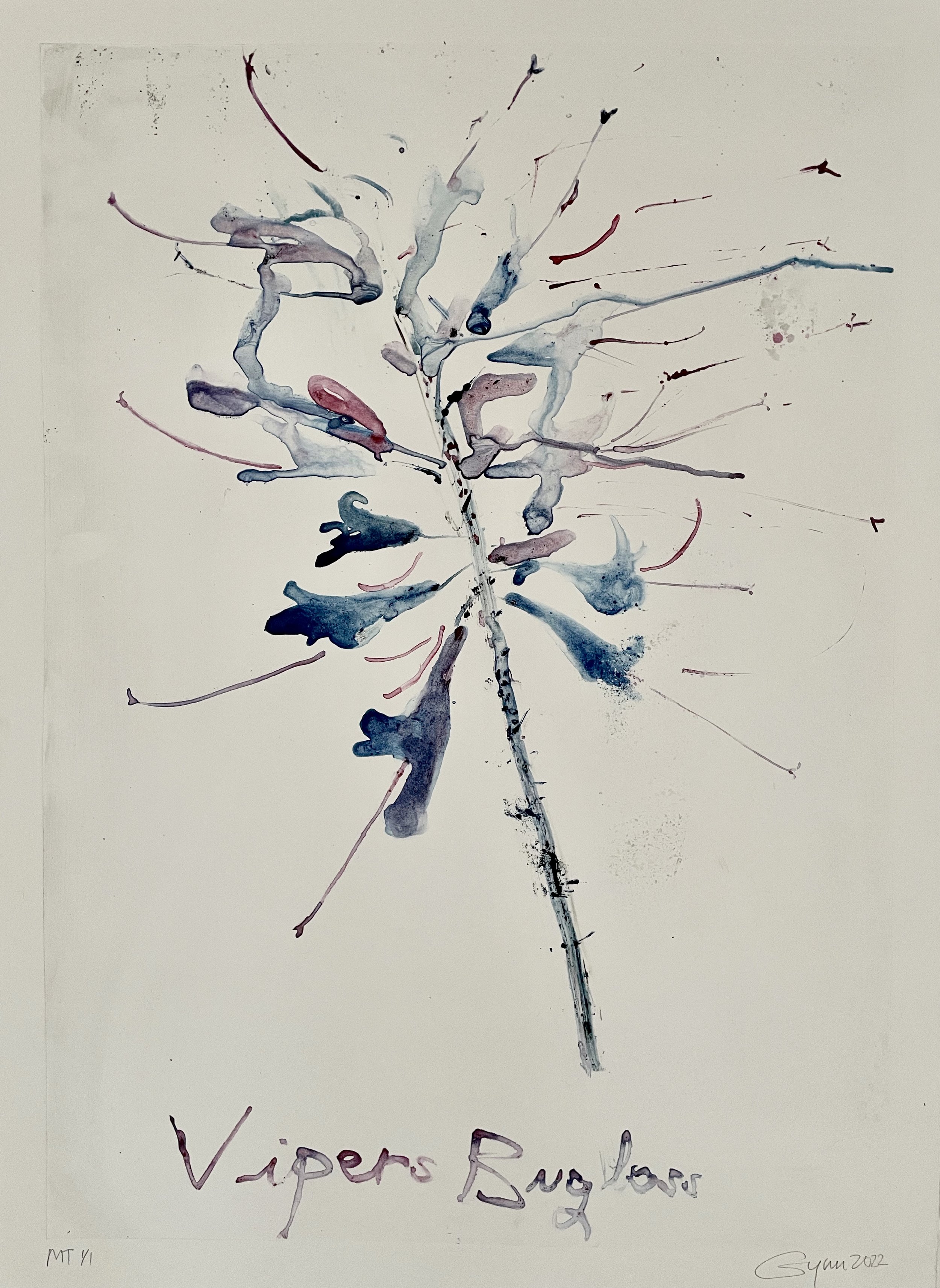

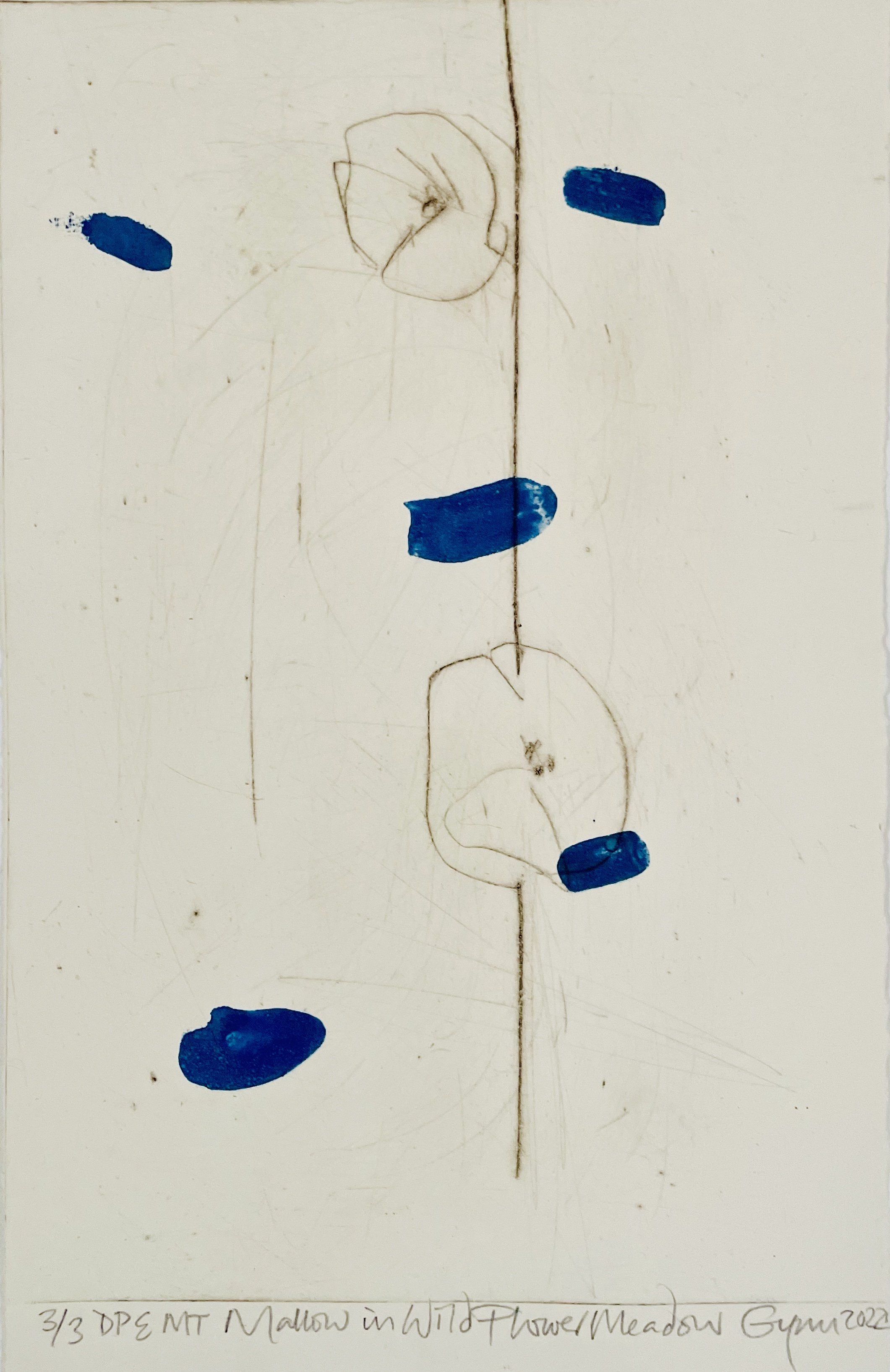

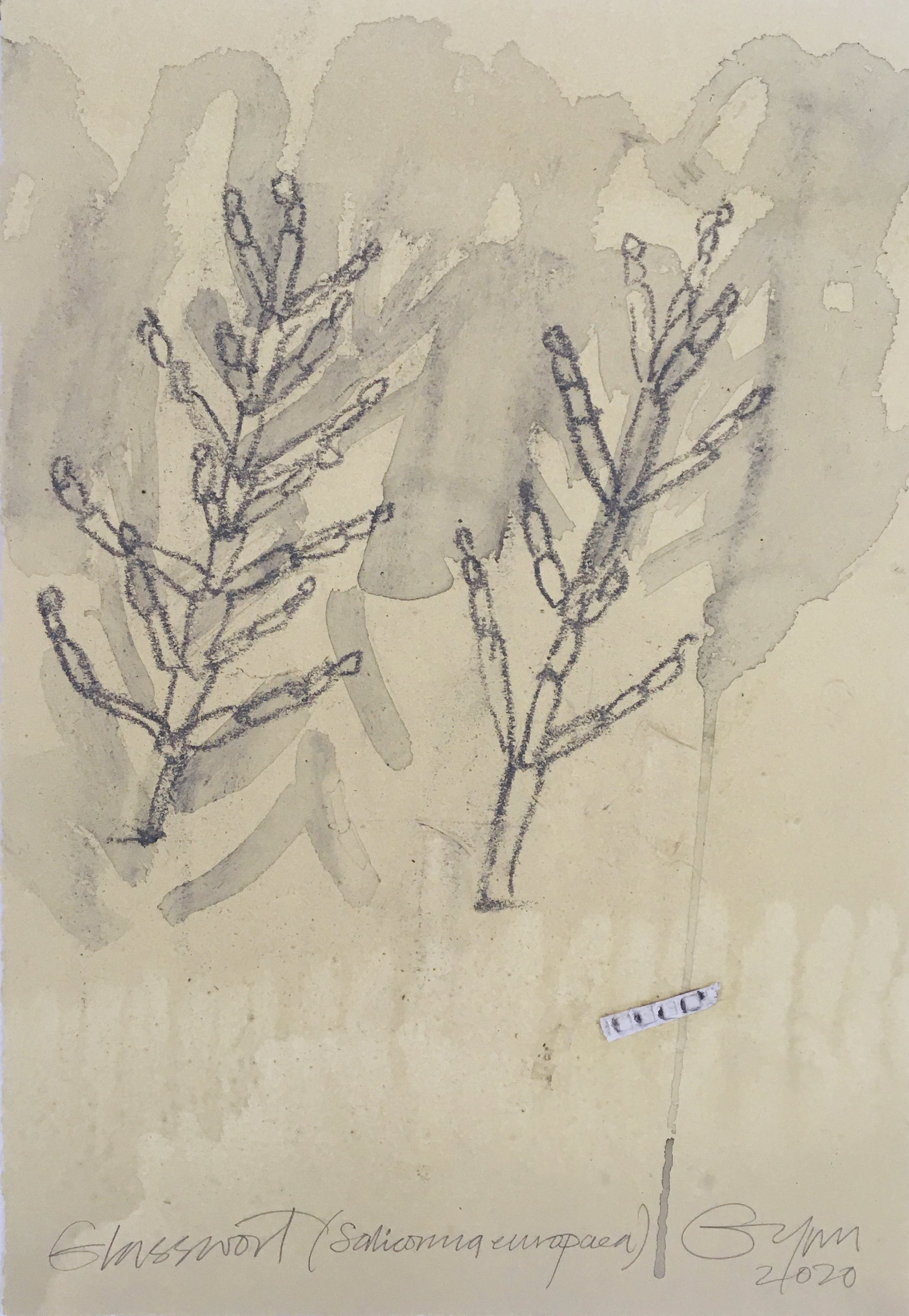

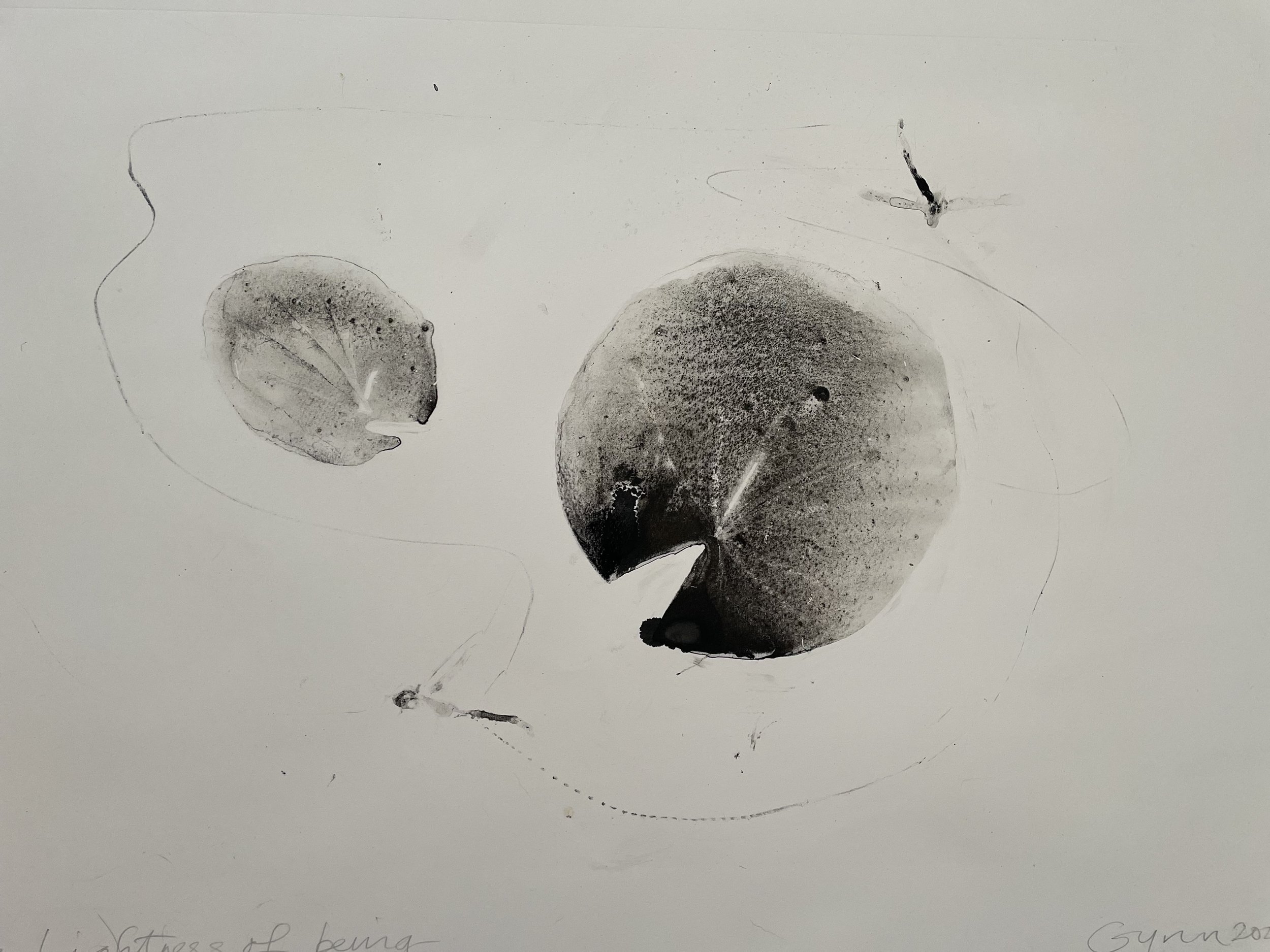

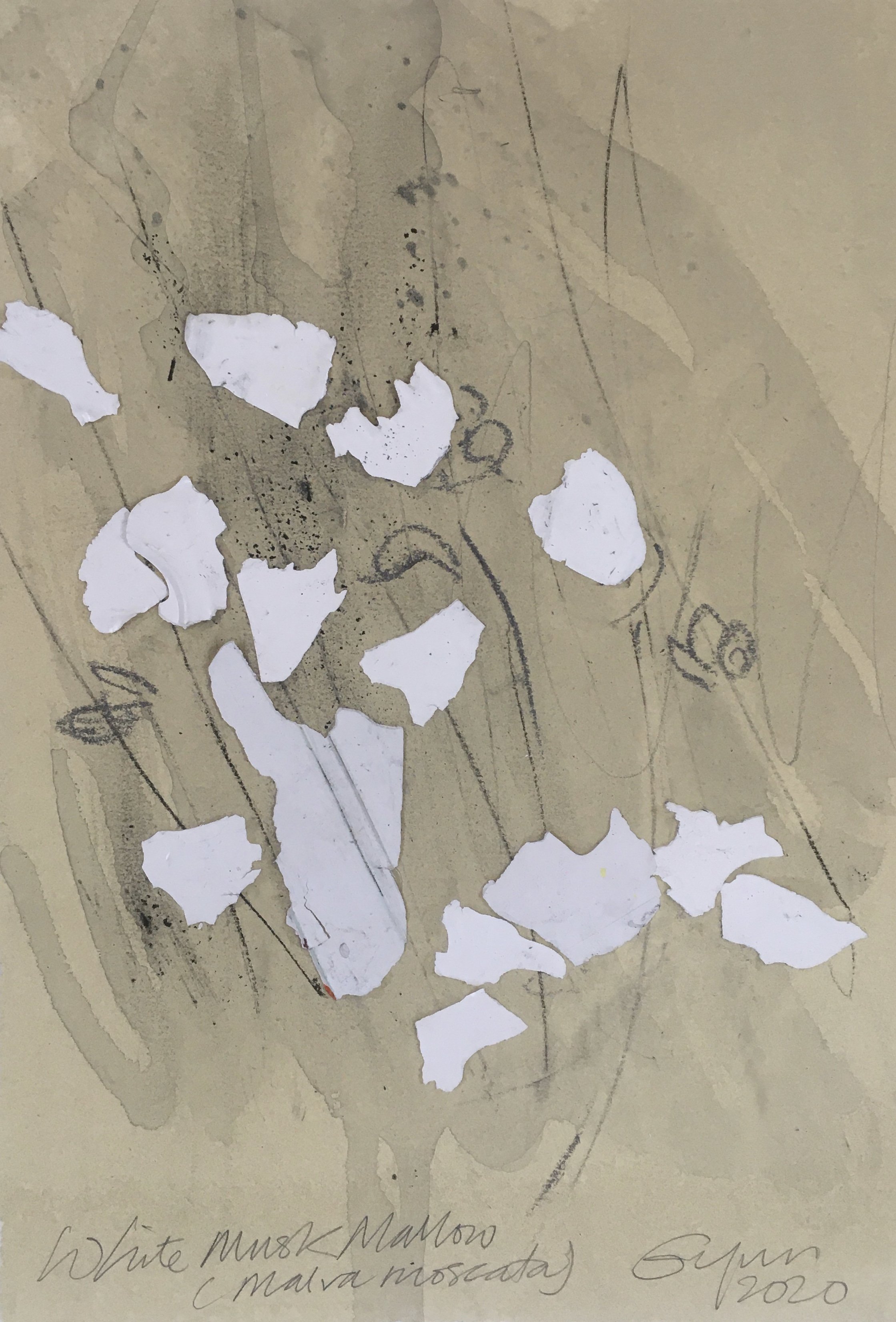

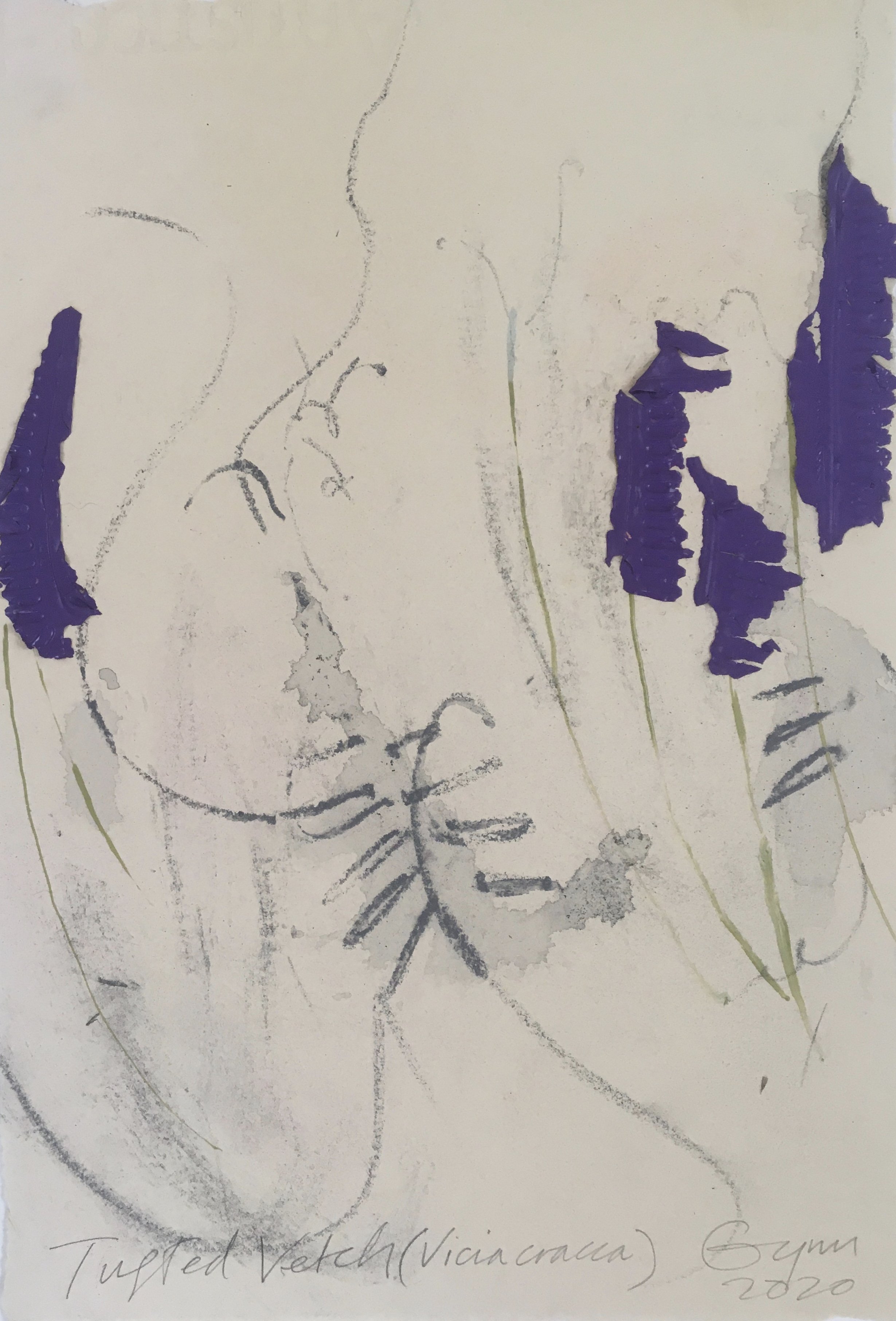

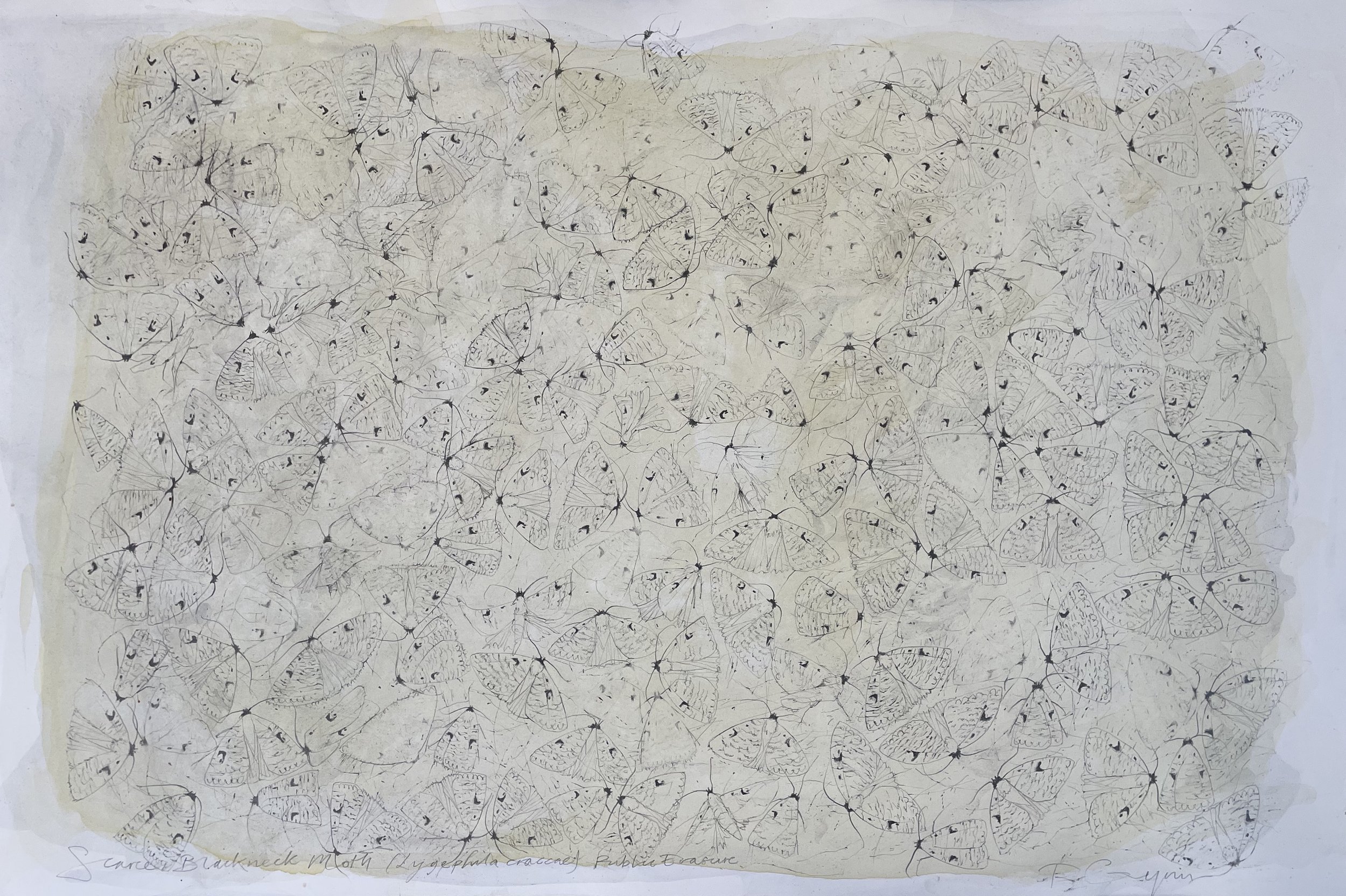

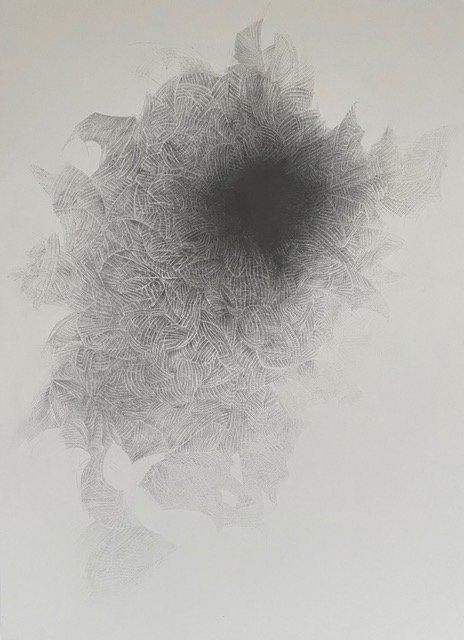

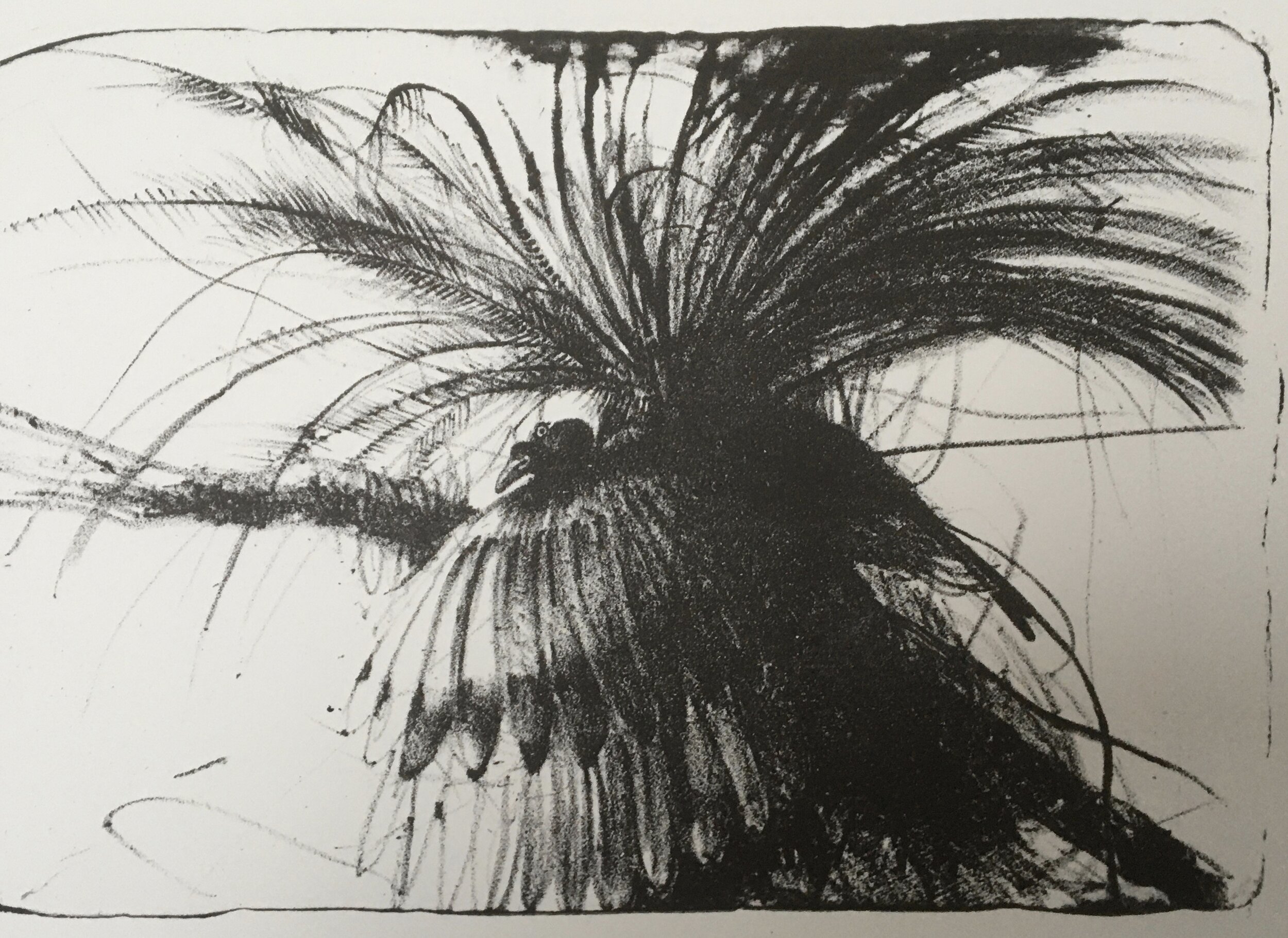

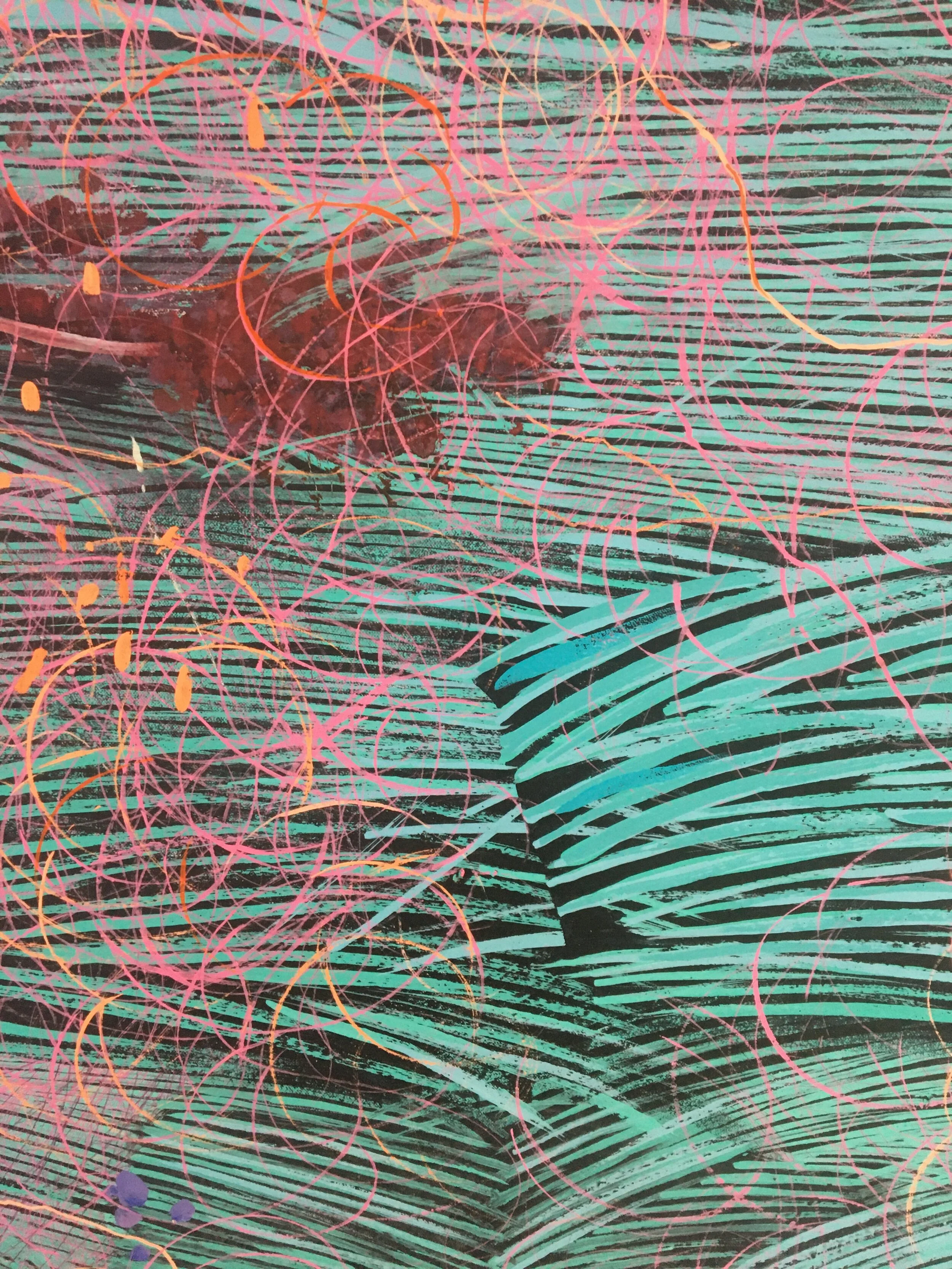

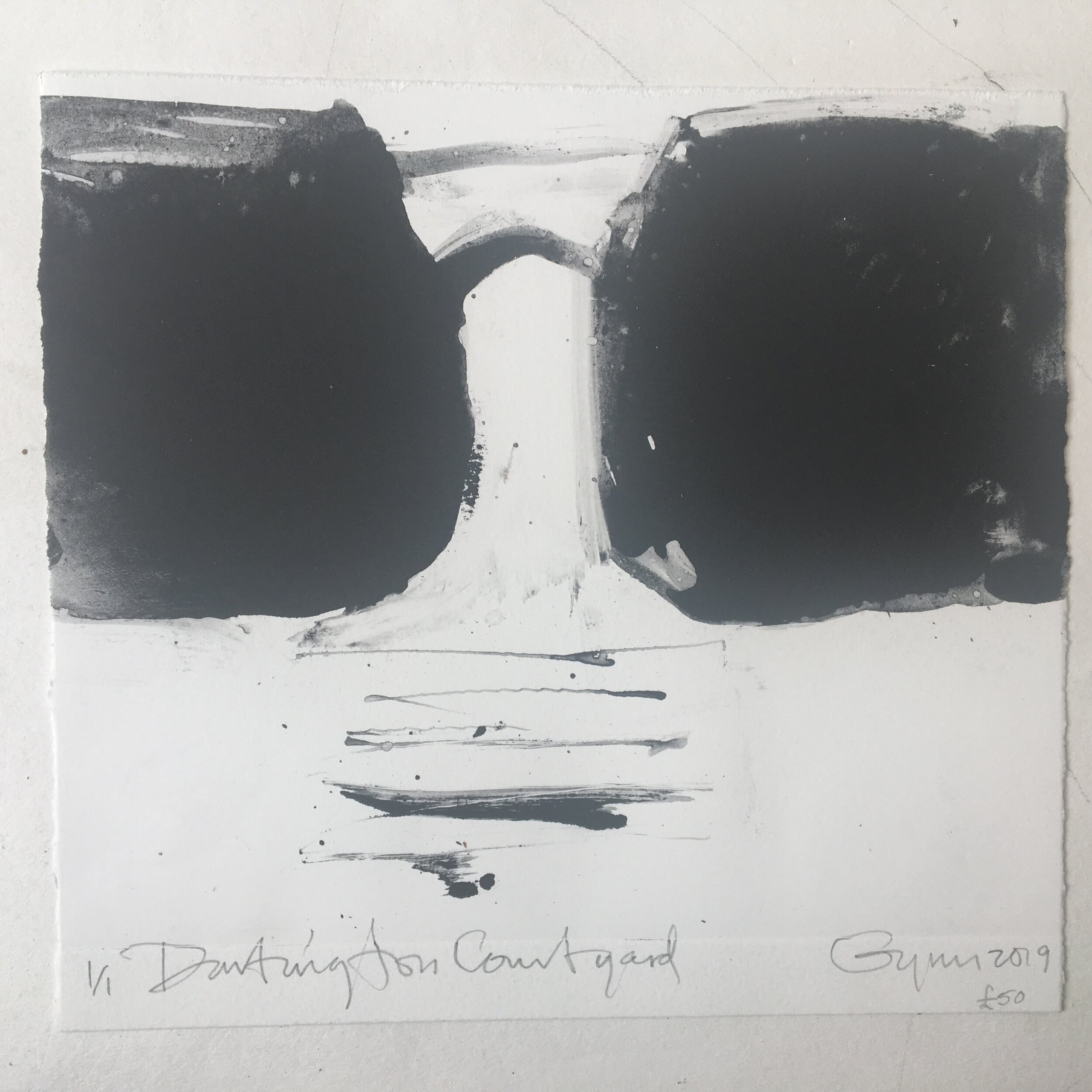

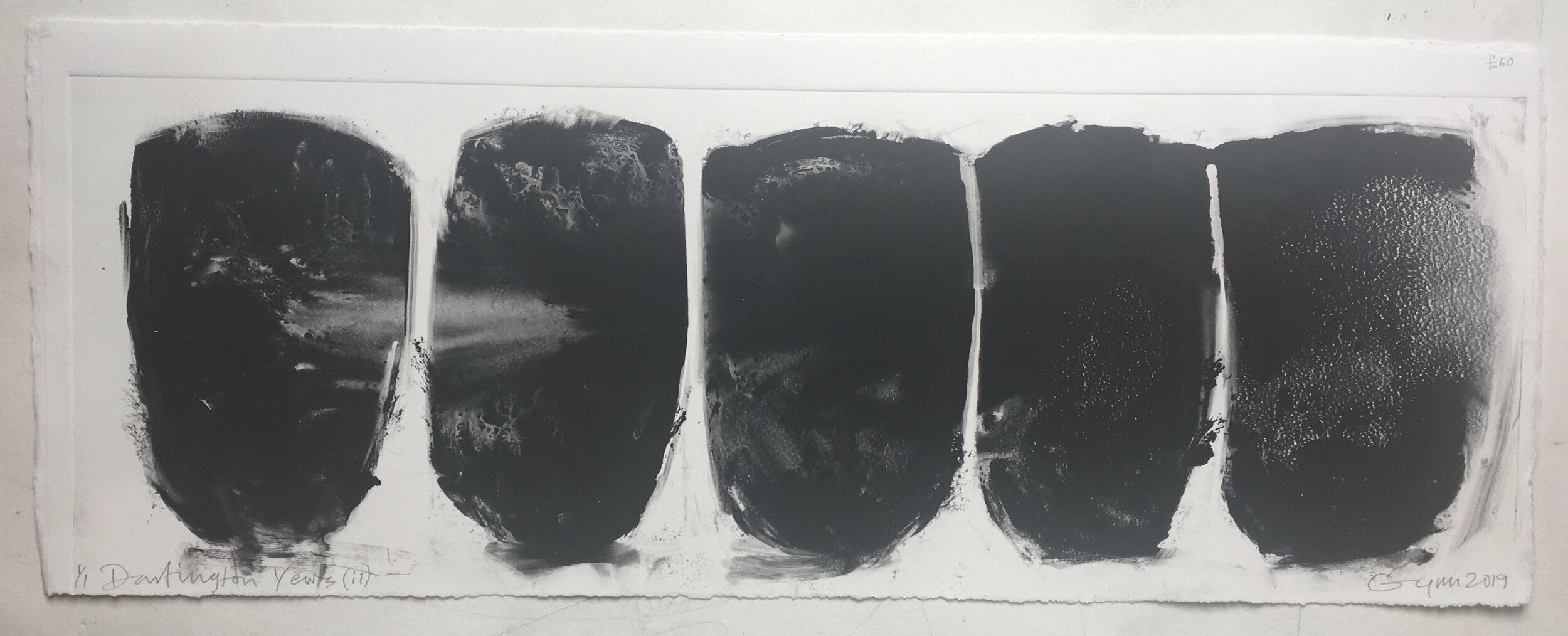

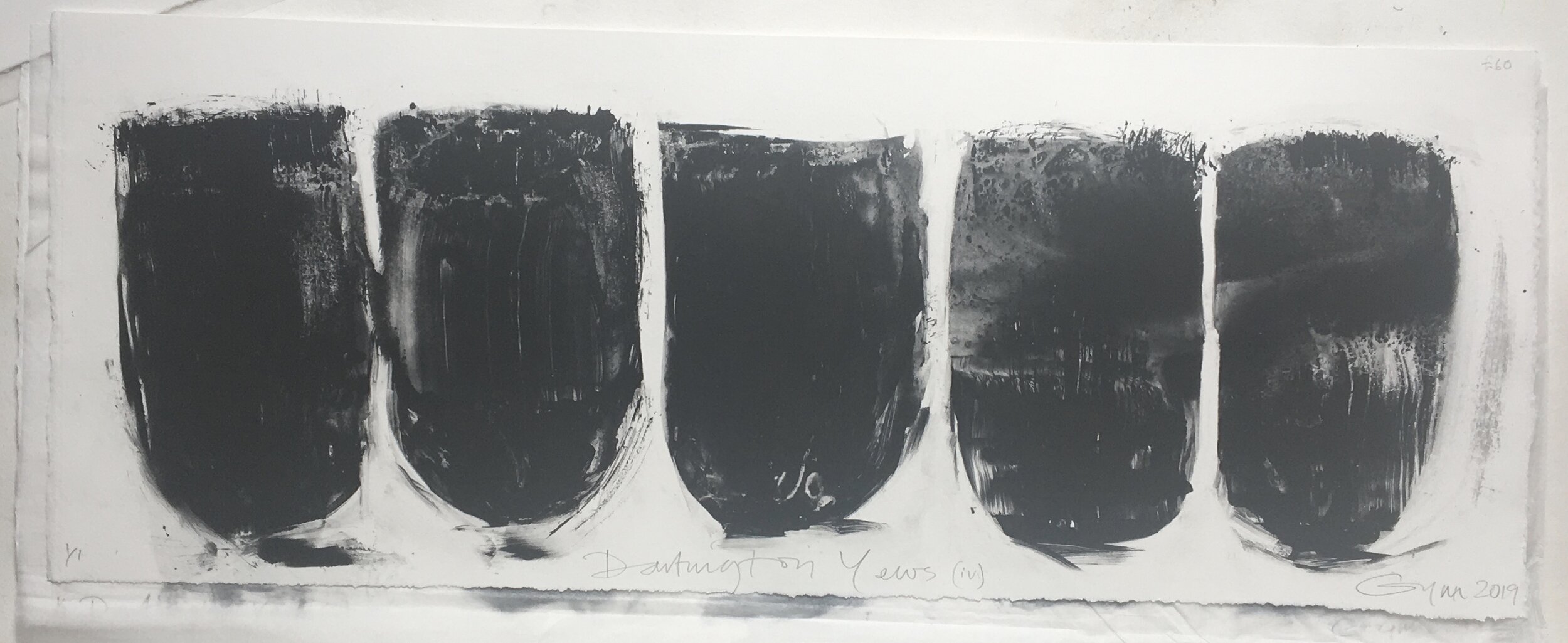

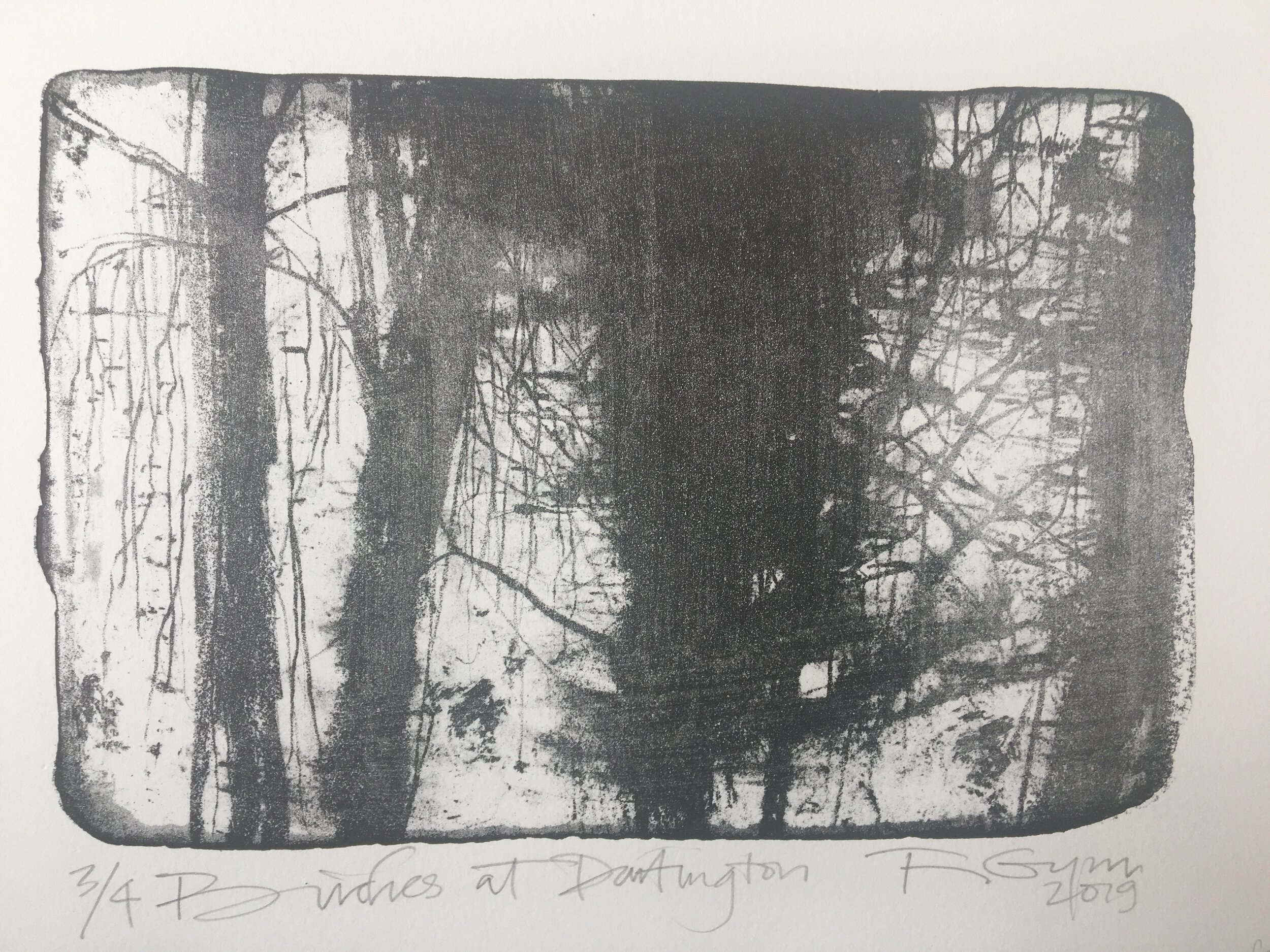

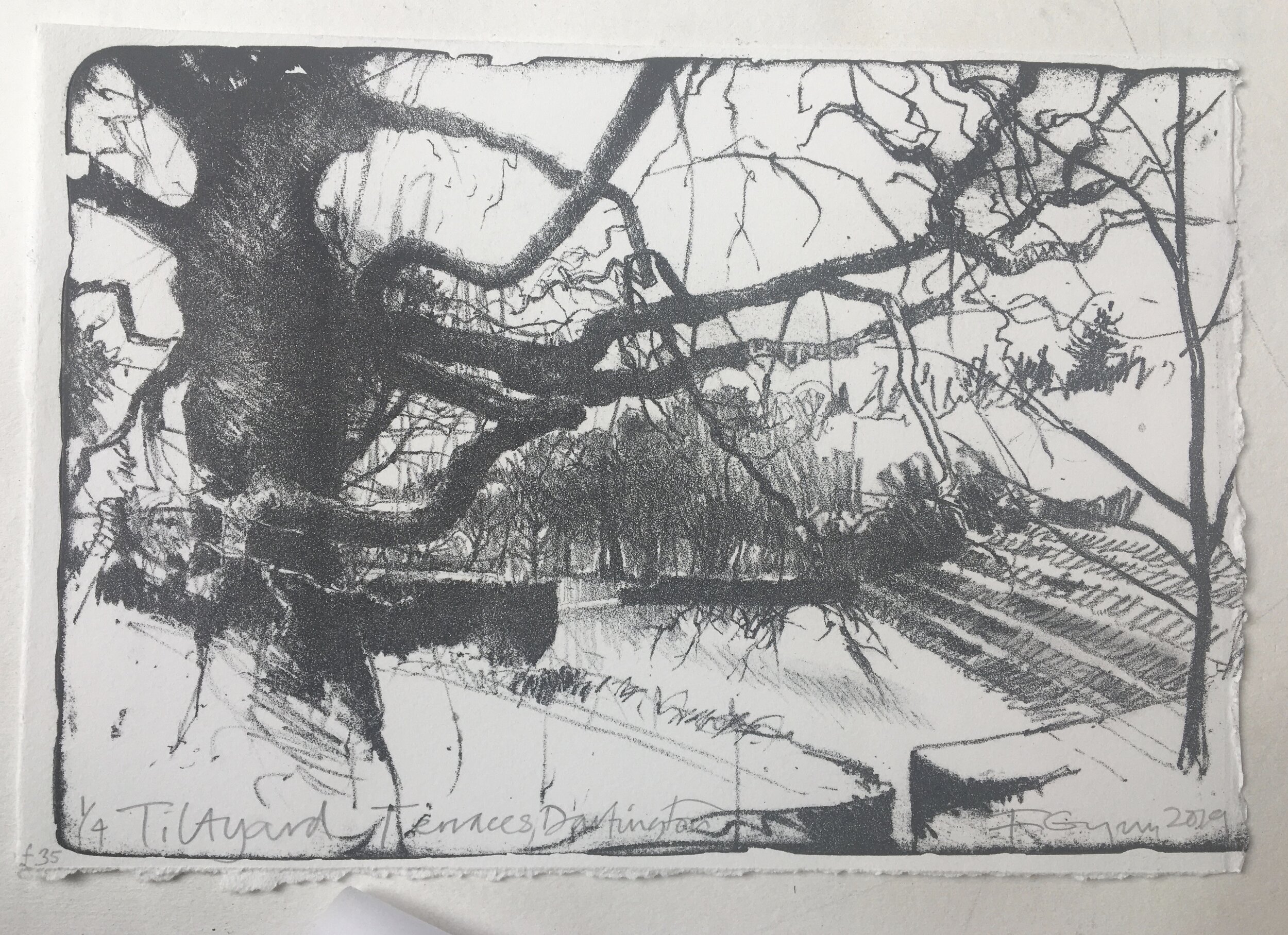

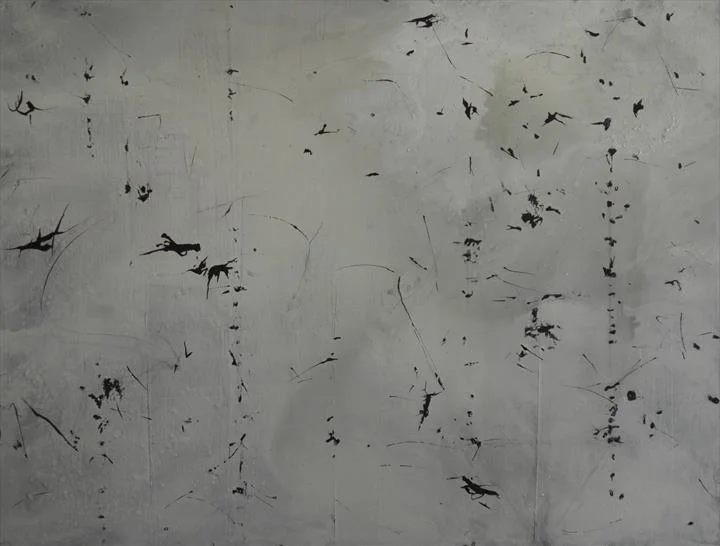

My practice is one of a study of transformation and the inherent beauty in that ceaseless, timeless process: transformation of objects by nature and man and the beauty found in that transformation. (FG)

My piano piece “The Ruined Village” (written for Hallsands Revisited) is as much about the spaces between notes as the notes themselves. The slow pace and the spaces between sounds are an invitation to slow down and listen. It’s not something we easily do these days. (LK)

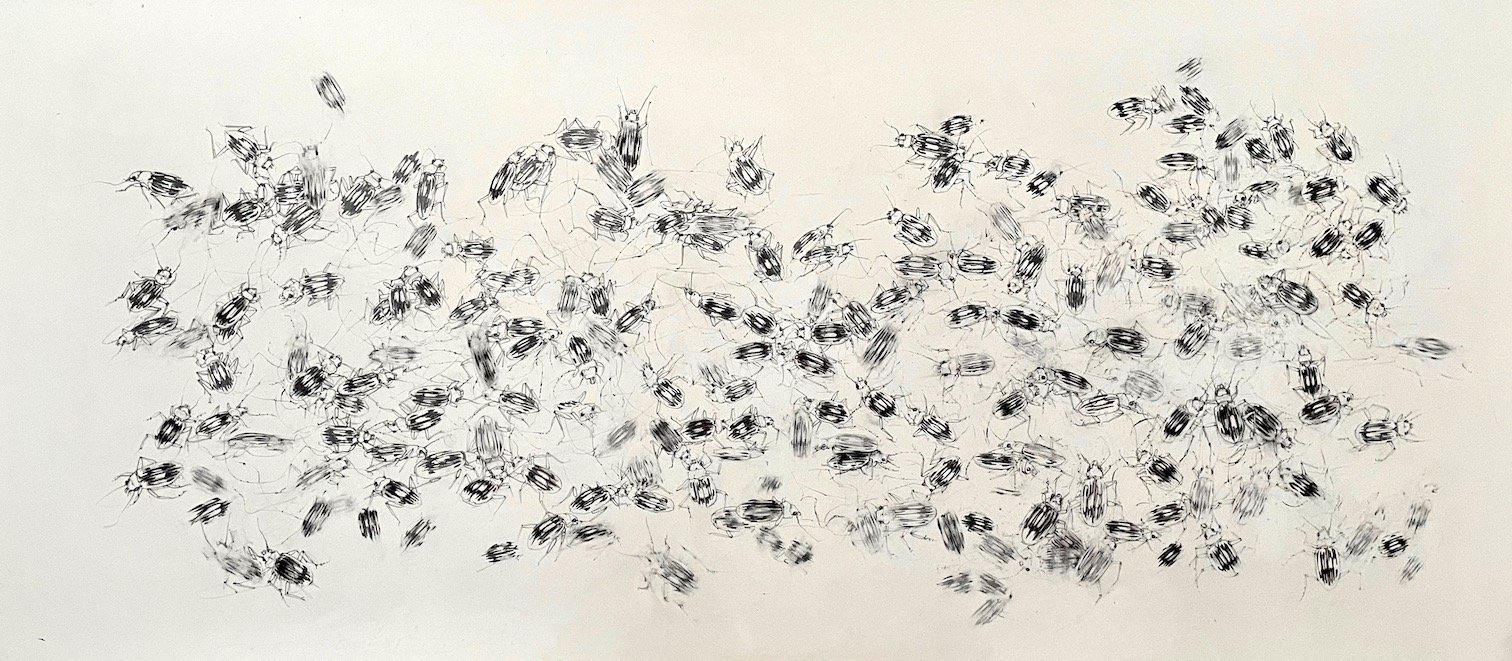

Beach flotsam and jetsam suggests a conversation, an event, a sensation. Drawing out and on the usability of ‘waste’ in the natural environment: discarded, reclaimed, colonised by nature to be washed up, reclaimed and transformed again. (FG)

The old fishing village of Hallsands is now a ruin. It can only be seen from a viewing platform, the rocks and cliffs now being unstable. It fell into the sea in January 1917.

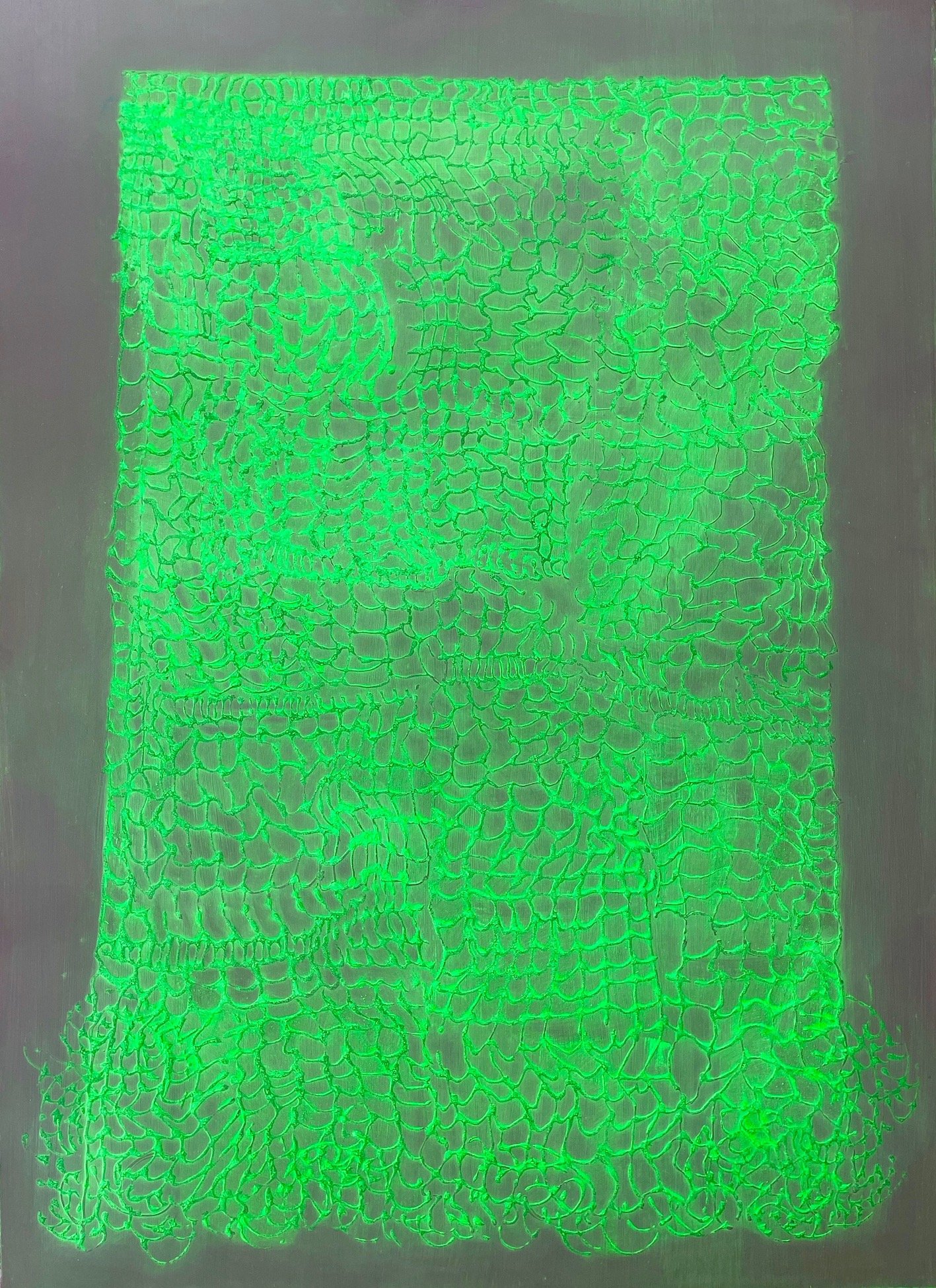

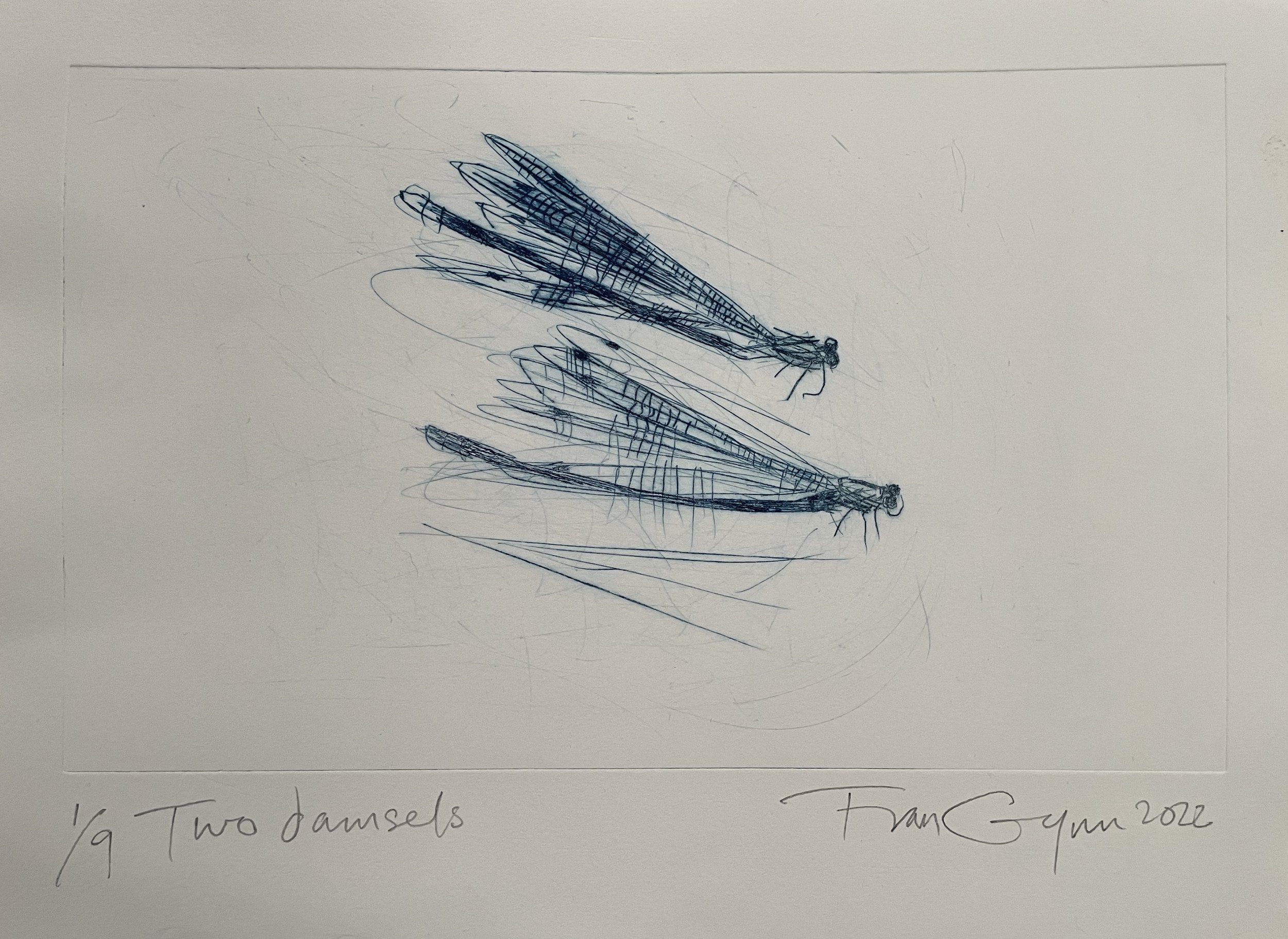

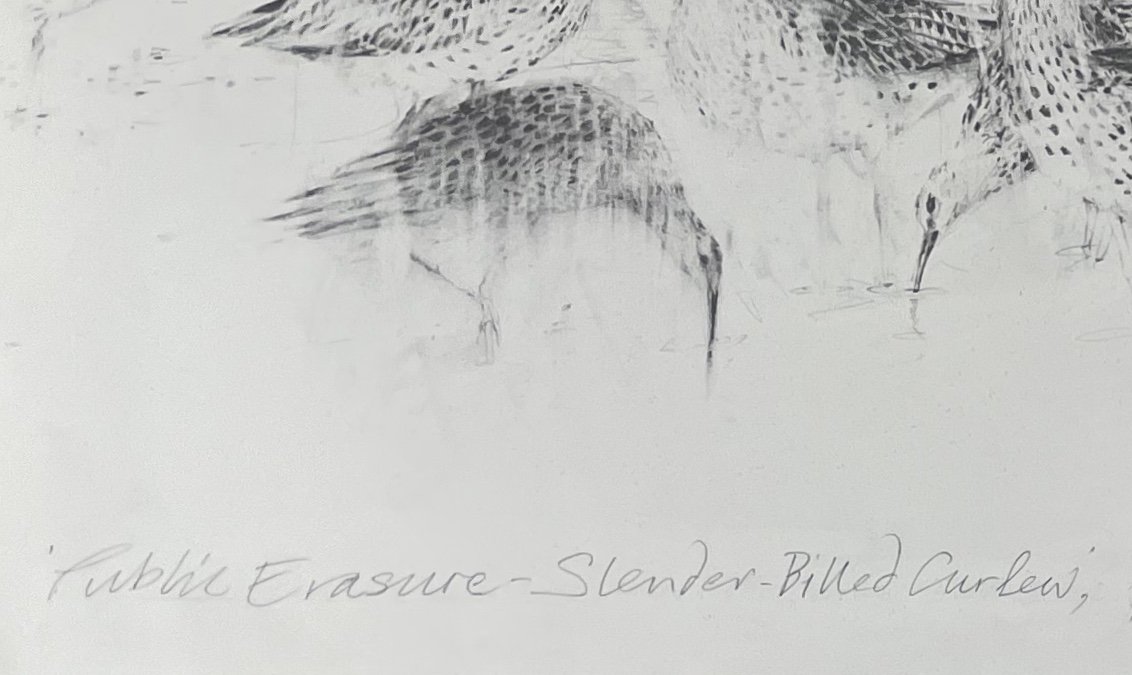

Having picked up bits of nets from the coastline here I discovered their name, ‘ghost fishing nets’ - derelict fishing gear that has been lost, dumped or abandoned. A big environmental concern. I had been using contour lines in my drawings to describe the lie of the land when fishing nets became a natural addition, which I now use to explore the characteristics of another, such as seawater or rock formation. (FG)

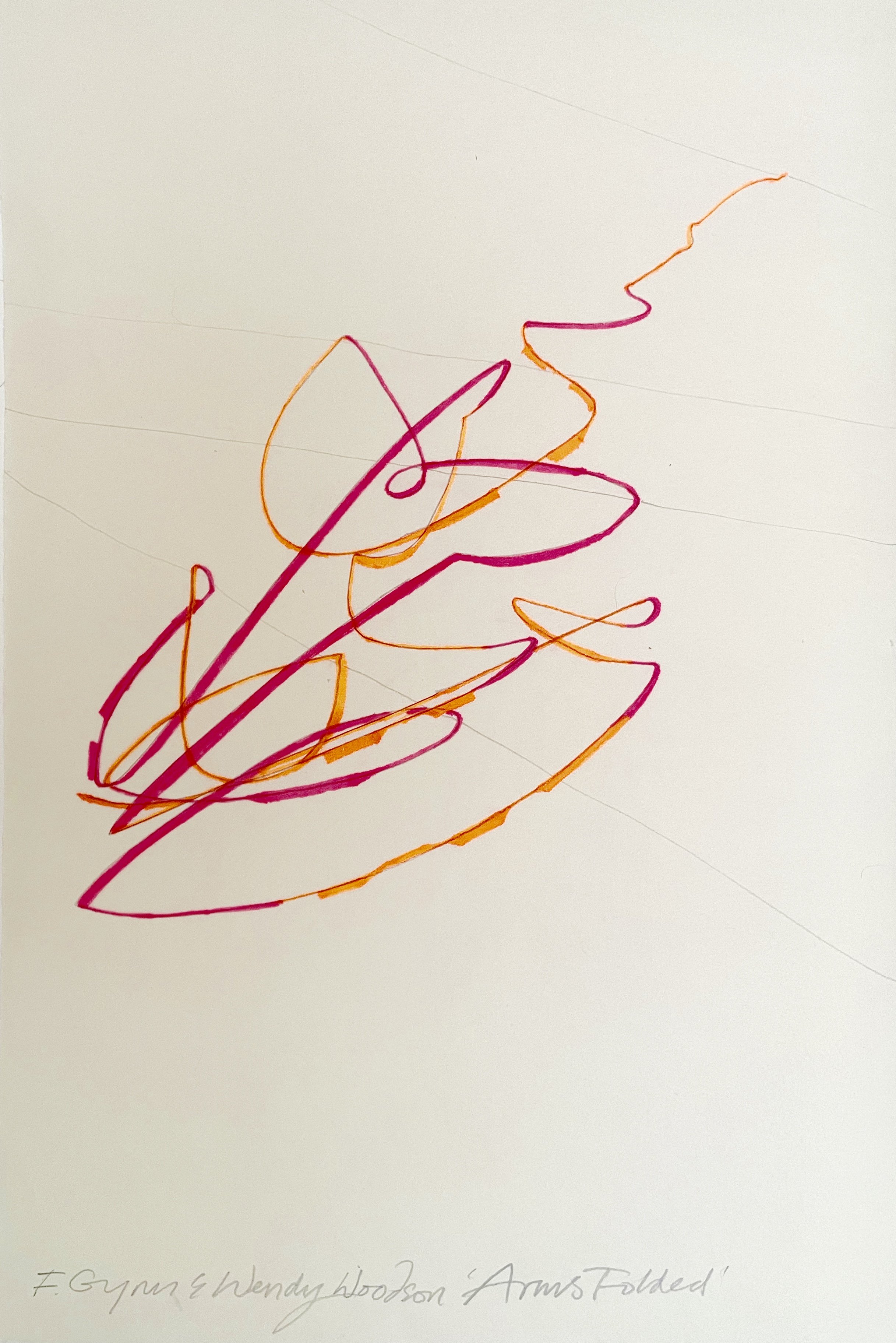

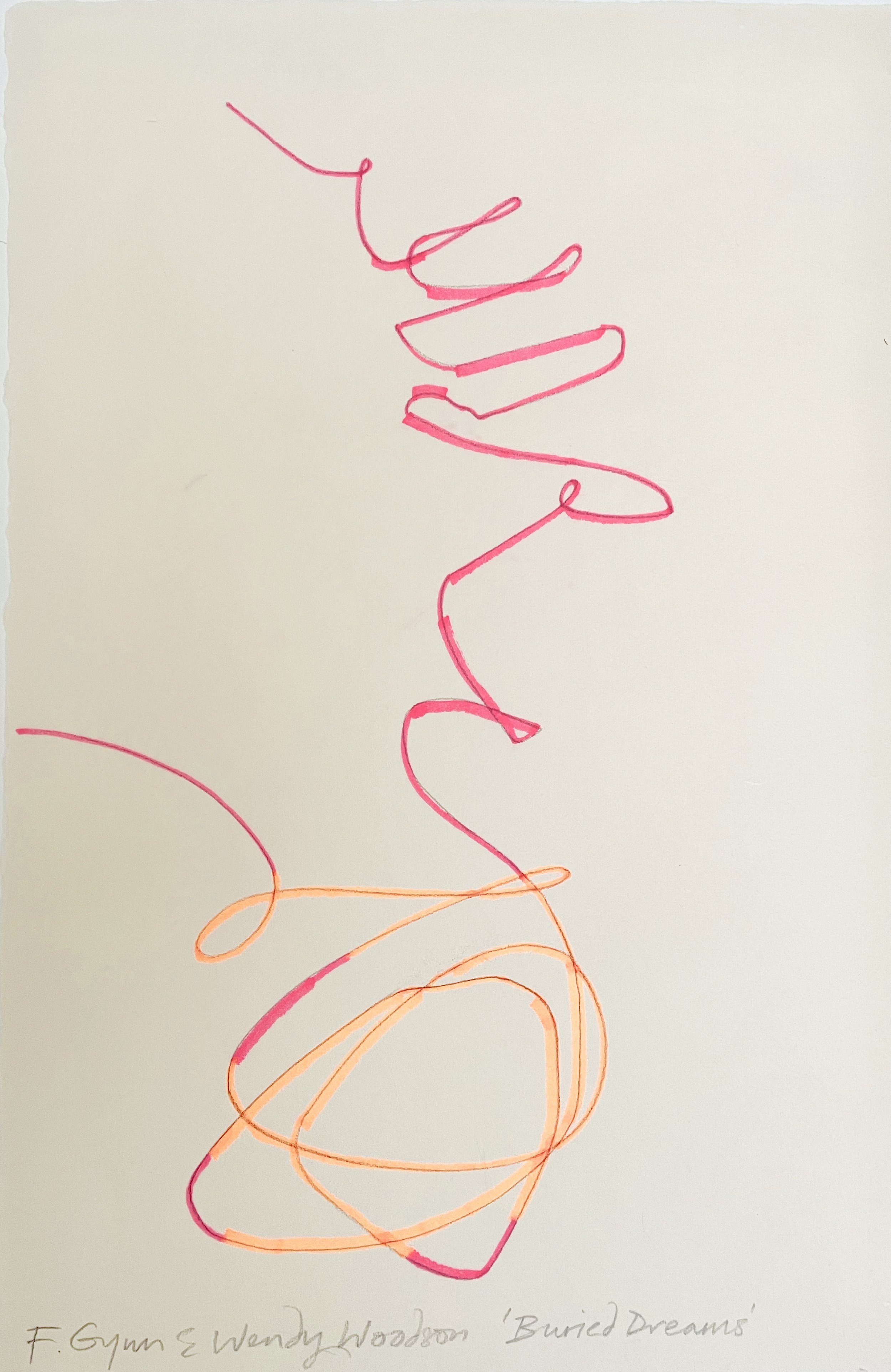

For our collaboration the three of us met weekly to improvise with sounds and with visual line. Fran had already become interested in the idea of nets.I thought of nets as being made up of many four-sided figures none of which are exactly the same. That’s an idea that’s easily translated into music. It also reminds me of lines from a poem by the artist, photographer and writer Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze). “The little waves in the harbour that repeat themselves without repeating themselves.” Nets and waves. I brought both ideas into our improvisations. (SR)

My improvisations are about depth and depths. They’re about hidden sounds, sounds literally hidden inside the piano, in or on the piano strings. They’re always in flux. Everything affects them – the time of day, the weather, whoever else is in the room (which includes audiences), whoever else is playing, everything. (LK)

Yes, it has been these ‘hidden sounds’ that have given me direct contact with Hallsands. A deeper immediate connection which isn’t normally there when I make a drawing or painting. Wonderful. (FG)

I am fascinated by the idea of nets, but it will be a much longer term project to write the piece I would like to write on this theme. One of the joys of a themed and collaborative project is that it does throw up ideas both for the present and for use later. (LK)

There is evidence of a settlement at the coastal village of Hallsands, South Devon, as far back as the beginning of he 16th century. By the late 19th century it had thirty-seven houses, a pub, a chapel, a reading room and a population of 159, nearly all fishing families specializing in crab fishing.

I have long had a fascination with Hallsands. Some years ago I made a radio docu-musical drama about it for live performance and for Soundart Radio. While I was researching I found Frances Gynn’s paintings on the subject. I already knew her and proposed some kind of collaboration (I knew not quite what) for 2017, the centenary of the final ruin of the village. (SR)

For several years I sketched and painted at Hallsands and when talking to Sam and Lona about a potential collaboration, the addition of another discipline to make work excited me. (FG)

You can listen with all your senses, not just hearing. It is a matter of opening yourself to everything around you. (LK)

Collaboration can be hard to get right. It can become a matter of one artform overwhelming the other. Or, as we have done, it can consist practitioners agreeing to operate in the same time and space, making artistic gestures derived from an agreed stimulus. Together we seek points of commonality and divergence. Parallelisms can result, but so equally can differences which can be left unresolved. Or not. The main thing is to step into the shared territory and see what happens. (SR)

I have a bag of tricks that I use inside the piano. I use fishing weights, ping-pong balls, e-bows, pencil top erasers and mallets. (LK)

What has most interested me about this collaboration is that the resulting drawings were in the beginning a complete surprise, ie I hadn’t preconcieved what was to come. This spontaneity was a joy, but for better or worse, we moved towards a more organised activity with my lines becoming more related to the assembly of nets and their physical characteristics, in line with particular musical values of Sam and Lona’s playing. (FG)

In the 1890s, in response to an Admiralty demand for new ships, Sir John Jackson obtained the contract to build a dock at Keyham in Devonport, Plymouth. Enormous amounts of shingle were required. Initially dredging was planned off Exmouth, but after objections from the Hon. Mark Rolle it was moved to Start Bay just off Hallsands. 1,600 tons were dredged daily. Local residents knew this would have a catastrophic effect on their coastline and beach, leaving the village unprotected.

I find my inspiration, setting and material on the seashore - manmade discards from far-off or contiguous, agglomerating with nature, drawing the viewer in to be part of the story of the world and the work. So here we have man’s intervention with both dredging and discarded ghost nets. The nature of nets is to trap, providing a metaphor for the collecting of sea stories told by the coastal community and the loss of Hallsands village . (FG)

Hallsands Revisited, for me, is part of a bigger purview that includes the Open University project I’m also involved in – Sounding Coastal Change which takes place on the North Norfolk Coast. It’s all about listening – listening to climate change, to local events, stories, events, catastrophes even. That’s the way all my work wants to go at the moment. (LK)

Ah yes, living on the sea front we’ve noticed storm frequency has increased however recent research suggests is the climax of a 30 year cyclical oceanic current pattern. (FG)

After protracted wrangles involving the Board of Trade, the local MP, the local Rural District Council, the dredging license was finally revoked in 1902, but it was too late. The damage was done. Storms and harsh winters eroded the village until in January 1917 a severe storm destroyed all but one house. Fortunately lives were not lost, although the locals spent many years trying to secure compensation.

I see both improvisation and composition as modes of listening. Improvisation is collaborative even if it is solo because everyone and everything present in is in it. (LK)

Hallsands strikes me as a kind of Brechtian story in the way that Brecht took historical or legendary material in order to provoke thought on contemporary issues. Human interference in natural ecology, the possibility that this might be damaging to the environment, local and expert warnings going unheeded, pursuit of unwise or uncertain courses of action in favour of “progress” or business interests, demonstrations and pleading, eventual disaster – this is hardly only a historical story. (SR)

Tragic though the loss of the village was, Hallsands has left us with a parable of human intervention in the environment, as well as extraordinarily evocative ruins and a rugged coastline where once was a beach. Both the tale and the locality provide unusually compelling material for artistic responses.

As each artistic statement is a moment in a continuous enquiry, or a journey without a destination, Hallsands Arts will undoubtedly unfold beyond Hallsands Revisited into future projects. One difference between a successful and an unsuccessful collaboration is that a successful one changes you, even if only a little bit, and you take those changes into future work. Therein lies some of the aspiration I have for an “after life” for Hallsands Revisited and the possibilities of Hallsands Arts. (SR)